DEGRADING

HUMANS

―

ARCHIVING

HUMANS

“Skulls were stored with care, apparently showing no trace of violence. But what are signs of violence? Were human beings not violated when they were placed in concentration camps? When their heads were severed from the bodies? When they were studied?”

Memory Biwa, historian

The attic of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics is where anatomical-anthropological collections were kept. Several thousand human and animal skulls and other skeletal remains were stored in cabinets there. In the basement, organs were preserved in liquid.

Scientists exploited conditions of social inequality, racial discrimination, and violence, in order to expand their collections. From clinics, they procured organs of deceased patients for whom no one could afford proper burial. From colonies, they stole the bones of the dead without the consent of living relatives. From those murdered in Nazi death camps, they sourced the body parts.

Uikabis and Nabnas

Among the human remains kept in the attic of the Institute were those of Uikabis and her daughter Nabnas. What little we know of these women is a story of violence. They both worked on a plantation in eastern Namibia in 1906, at that time colonised under the name “German South West Africa”. One day they fled. The German plantation owner Paul Wiehager had them arrested and bound. They were given neither food nor water. Nabnas died of thirst, and Uikabis was hanged the following day. The farmer was tried, and Uikabis’ and Nabnas’ bodies were kept as “evidence”.

After the trial, anthropologist Felix von Luschan acquired the two women’s remains. In 1927, one of his collections was transferred from the University of Berlin and given to the Institute at Ihnestraße 22. Included in the collection were the human remains of Uikabis and Nabnas. After many changes of location, they were returned to Namibia in March 2014. We do not have access to a photograph of these two women in life.

Shrouding of the boxes containing human remains, by Nzila Marina Mubusisi, Chief Curator of the National Museum of Namibia, 2014

EPA/Soeren Stache

Two of these 21 boxes contain the mortal remains of Uikabis and Nabnas. Here they are being prepared for their repatriation to Namibia. Until this point, they had been at the Charité Hospital in Berlin. After repeated demands from affected communities in Namibia, they were returned in March 2014.

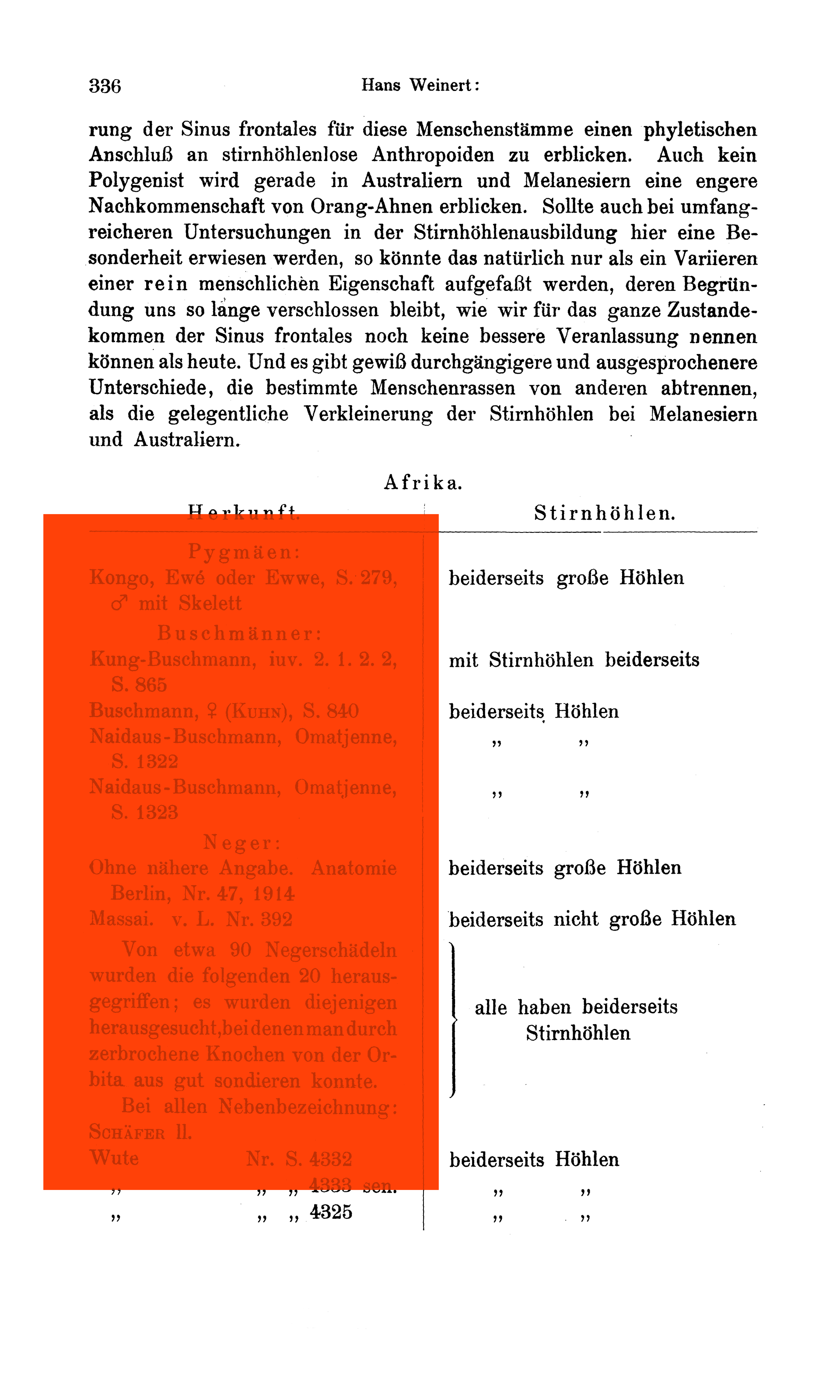

Hans Weinert

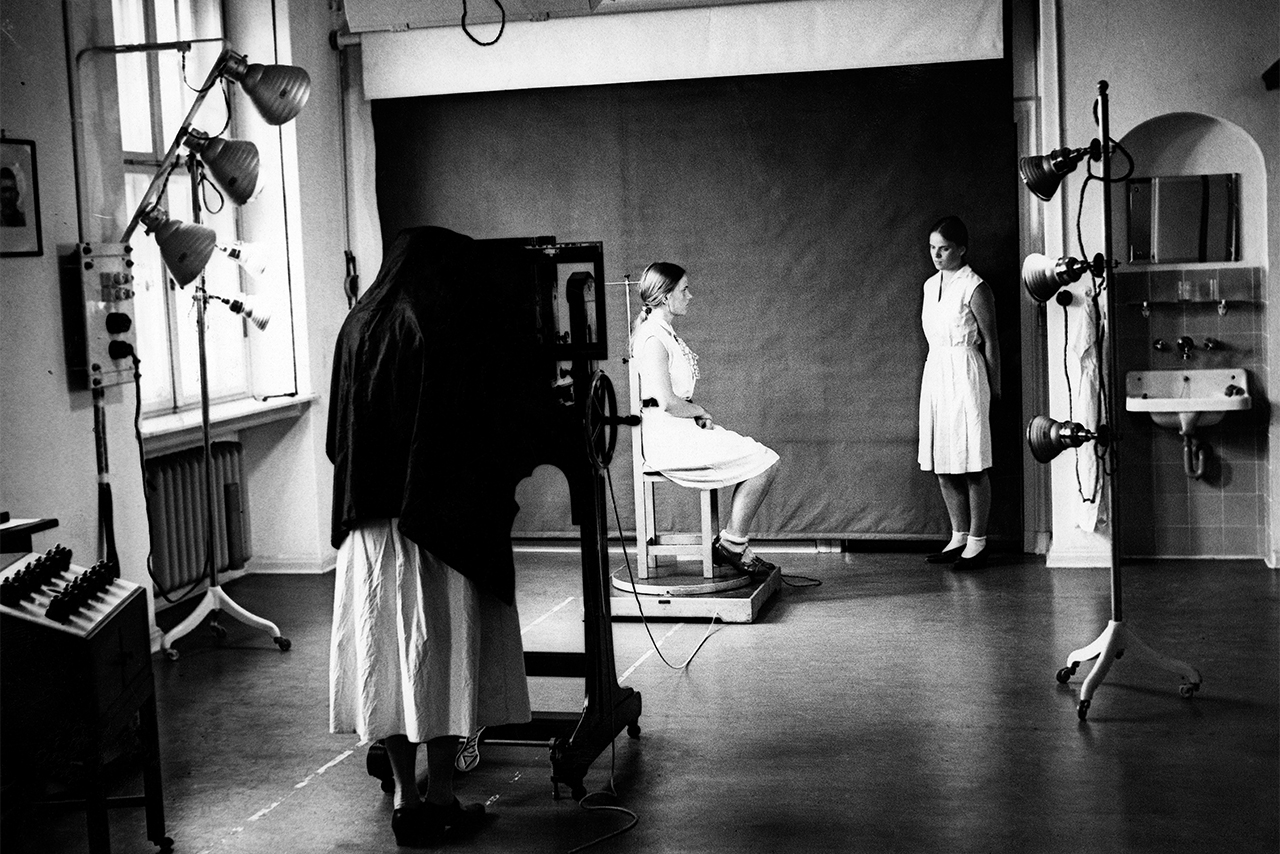

Between 1928 and 1935, Hans Weinert (1887-1967) curated the Institute’s anthropological collections. His research focused on human evolutionary development. Although he acknowledged that all humans shared a common ancestor, he was nevertheless convinced of the superiority of White people.

From 1935 on, Weinert taught as Professor of Anthropology at Kiel University. On the side, he authored so-called “racial-biological expert reports”. Many of these reports resulted in beneficial classifications for those examined, shielding them from persecution as Jews. However, Weinert demanded exorbitant fees for his services. After the War, women accused Weinert of sexual assault. Nevertheless, he remained a professor until his retirement in 1955.

Hans Weinert, is dressed in a dark suit and surrounded by young scientists from the Institute. On the table and in the hands of the doctoral candidate, Irawati Karvé, are specimens from the Institute’s collection.

In the collection, Uikabis and Nabnas existed solely as objects with collection numbers: “S 1322” and “S 1323”. In the 1920s, Hans Weinert conducted research on them. He wanted to determine the evolutionary relationship between humans and apes and, to this end, measured the frontal sinuses of skulls.

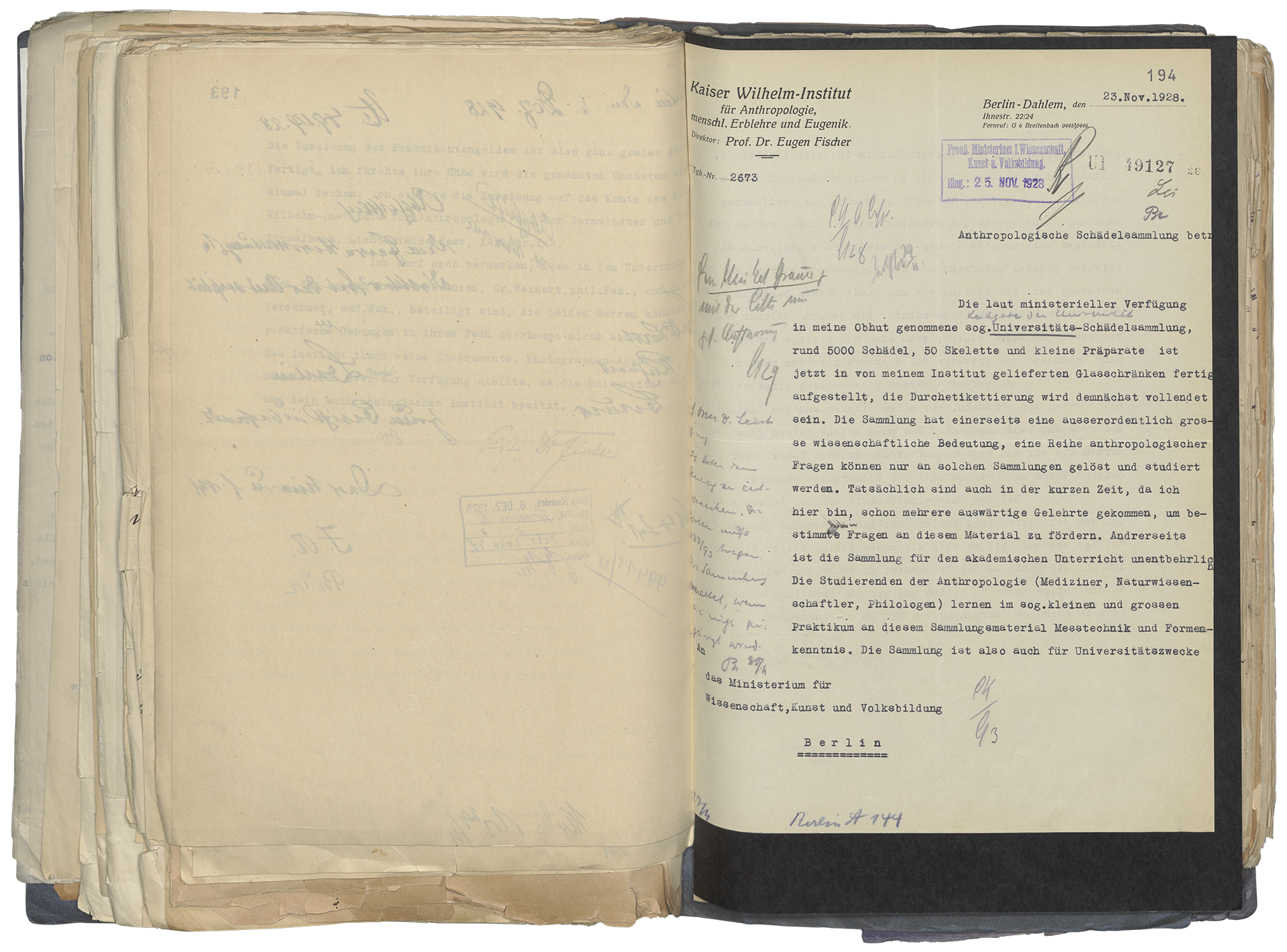

A colonial collection

The largest collection at the Institute consisted of the remains of approximately 5,000 individuals from all continents. Director Eugen Fischer acquired them from Felix von Luschan, his predecessor as the Chair of Anthropology at Friedrich Wilhelm University Berlin (now Humboldt University). Luschan had primarily acquired remains during the German colonial era. In Dahlem, the collection was continuously expanded and used for research purposes.

Mapping humanity

In the early 1940s, Eugen Fischer planned a “Central Genetic Collection”. For this purpose, he primarily acquired animal and human embryos. Scientists sought to use these embryos to investigate how specific traits and diseases developed. The collection was intended to bring the entire human population under one roof at the Institute and organise it based on human genetic principles.

Acquisition of human remains from Nazi concentration camps

From 1943 on, Wolfgang Abel was permitted to conduct research on Soviet prisoners of war in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin. This is one of many indications that members of the Institute probably also collected body parts from individuals who were murdered in Nazi camps. From 1942 on, Abel planned to establish a “Teaching Collection on the Racial History of Europe and the World” at the university of Berlin.

Dehumanisation of the living and the dead

Since 2014, human bone fragments have been excavated from the former grounds of the Institute. It is most likely that they originate from the anthropological collections once stored in the attic of the building at Ihnestraße 22. We do not know the names or stories of the humans they belonged to.

What does it mean that bones were found in this and other places?

Video commentary by

Israel Kaunatjike, OvaHerero representative, Berlin

02:41 min.

What do we know about the bones found onsite?

Video commentary by

Prof. Dr. Susan Pollock, formerly at Freie Universität Berlin

2:43 min.

What do we know about the “S-Sammlung” and what is happening to it today?

Video commentary by

Dr. Bernhard Heeb, Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

2:25 min.