RESEARCHING

DISABILITY

―

CONSTRUCTING

DISABILITY

Hildegard B.

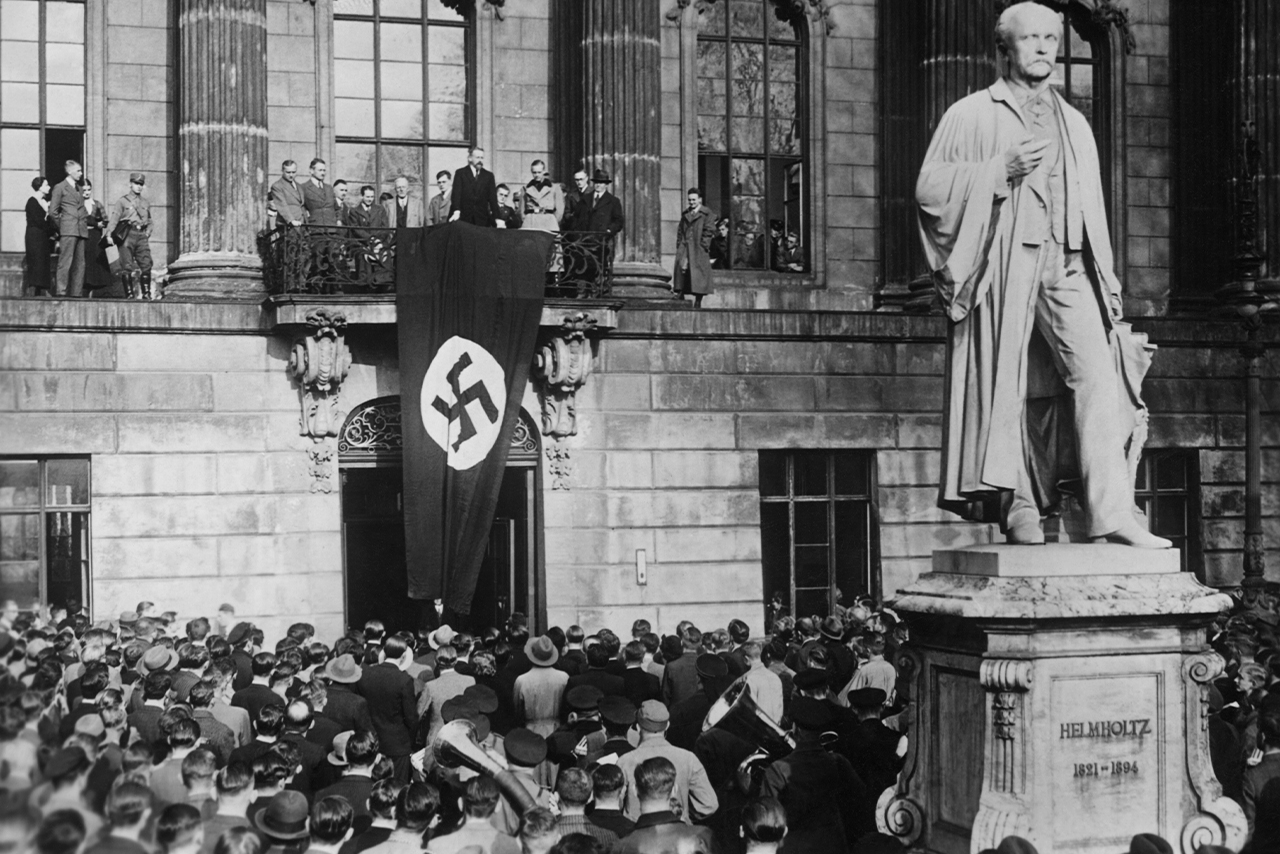

Hildegard B. was born in Berlin in 1922 and grew up under impoverished conditions. She was described as restless and defiant and experienced violence at the hands of her stepfather. Her mother wanted to place her in foster care. In 1934, a public health officer diagnosed Hildegard B. with “congenital imbecility”. The diagnosis was based on “intelligence tests” designed to meet an educated bourgeois knowledge standard. This diagnosis was the most frequent grounds for forced sterilisations under National Socialism, impacting many impoverished and socially marginalised people.

Following her diagnosis, authorities admitted Hildegard B. to the Wittenau Sanatorium. In 1938, she was sterilised by force. She suffered for weeks after the operation. In February 1939, Hildegard B. was transferred to the Meseritz-Obrawalde Asylum in Posen. In June 1941, she was transferred onward. It is highly likely that she was taken to a killing centre and murdered there as part of the anti-disability campaign “Aktion T4”.

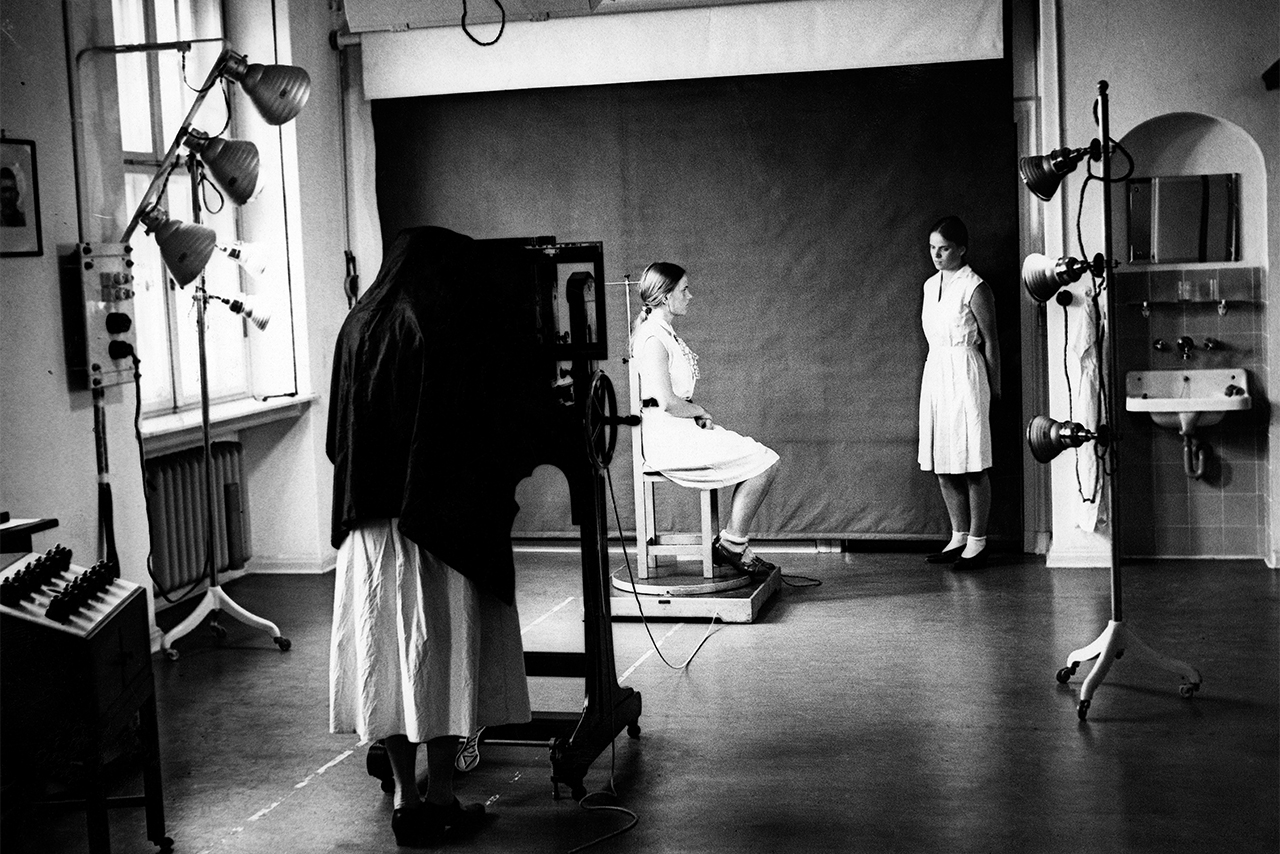

Photo of Hildegard B. from her patient file, 1937

Federal Archives, Berlin, R179, 6327

This photo of Hildegard B. was probably taken in the Wittenau Sanatorium without her consent. Standardised photos were taken to recognise and compare patients. When this picture was taken, Hildegard B. would have been nearing her 15th birthday.

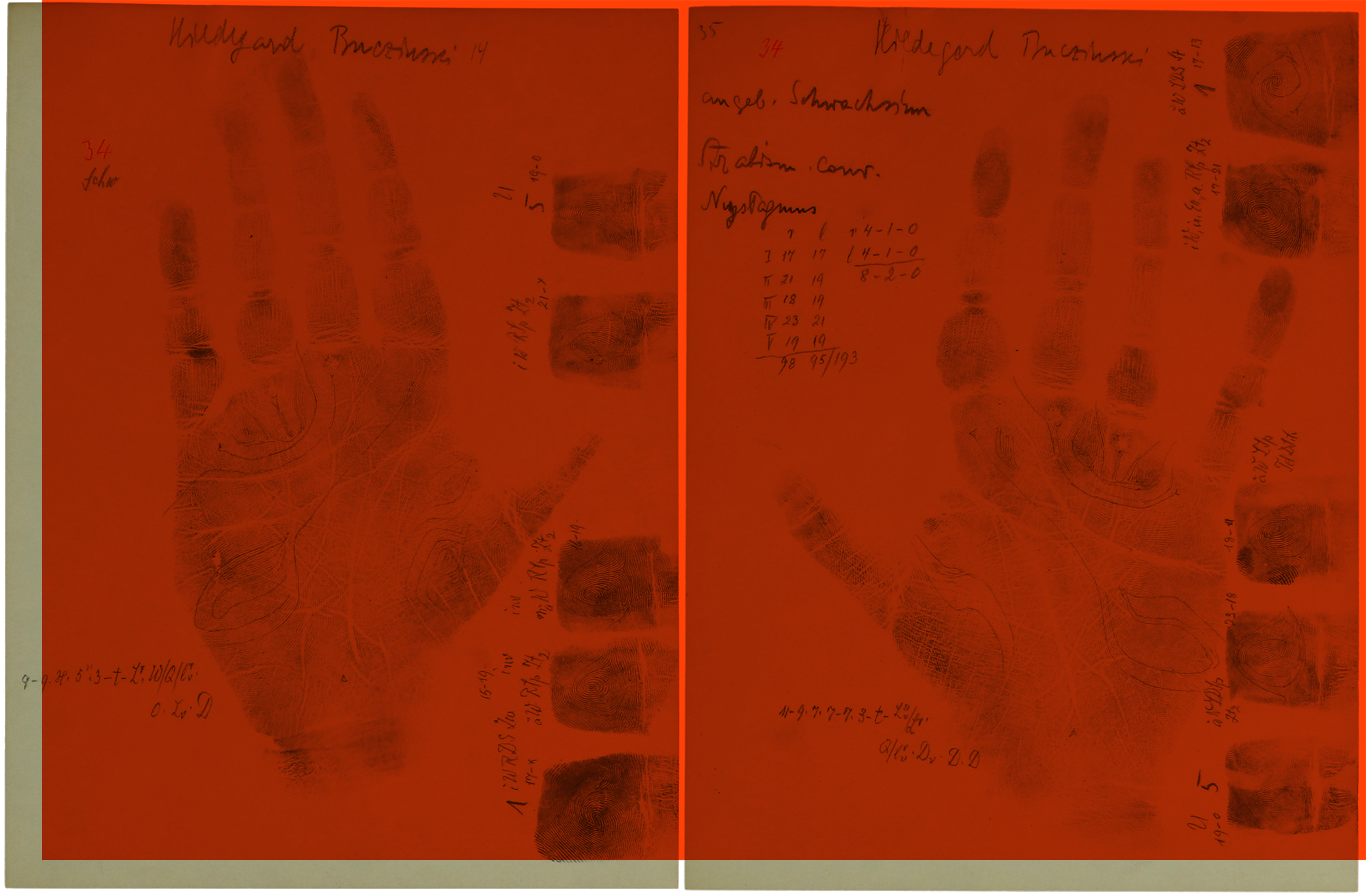

Prints of Hildegard B.’s hands, 1936

Archive of Max Planck Society, Berlin-Dahlem, Nachlass Geipel, Abt. III., Rep. 048/036, Nr. 235 und 233

Hildegard B.’s handprints were taken at the Wittenau Sanatorium. She was 14 years old at the time. The diagnosis “congenital imbecility” is written on the prints. Georg Geipel examined the handprints. He believed he could find characteristics of the diagnosis in the palm lines.

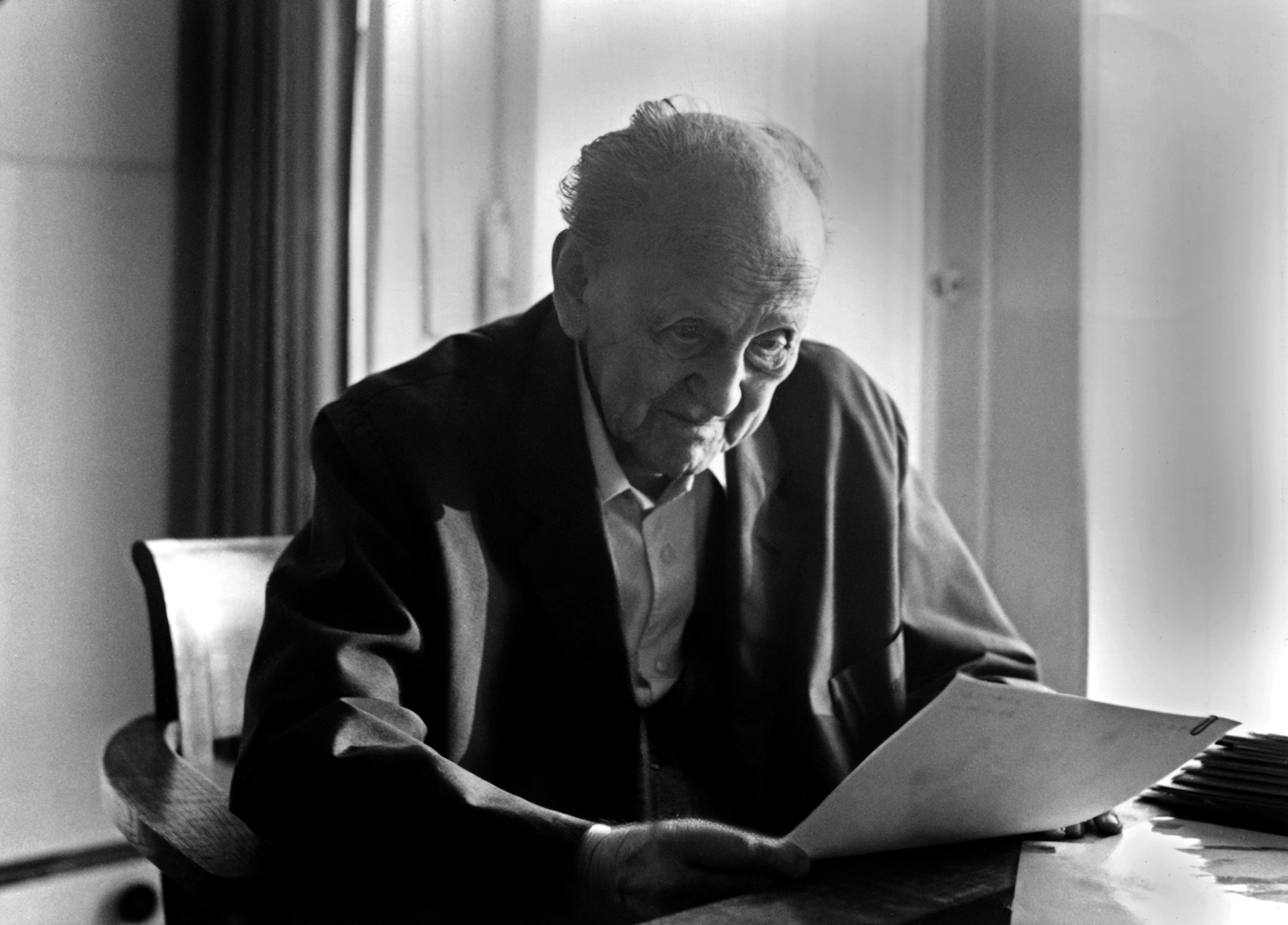

Georg Geipel

The teacher Georg Geipel (1871–1973) embarked on his career as a scientist only after his retirement. From 1930 on, he worked at the Institute, where he became an expert in dactyloscopy: the study of patterns in human finger-, hand-, and footprints. Geipel deduced alleged “hereditary diseases” from these patterns, using them to categorise people according to “race” or “dis- ability”.

Prints were sometimes taken from people forcibly and without their consent. After 1945, Geipel continued to work at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Genetics and Hereditary Pathology (today the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics).

What does the story of Hildegard B. have to do with us today?

Video commentary by

Peter Mast, Kellerkinder e.V.

2:20 min.