FROM

CLASSIFICATION

TO

STERILISATION

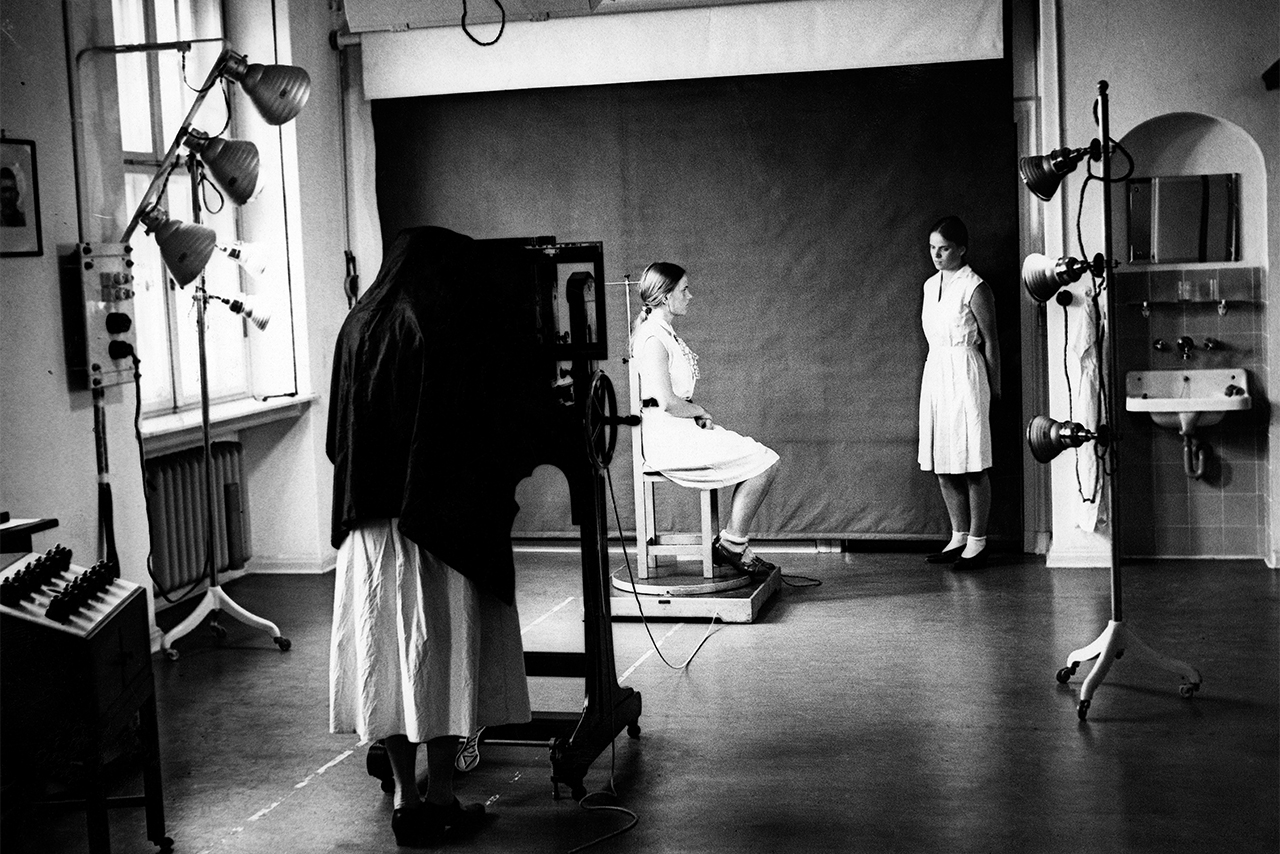

Institute staff sorted out individuals from the general population: Those who were considered “hereditarily ill” would not be permitted to have children. As early as 1932, Hermann Muckermann drafted a sterilisation law. The Nazis not only implemented the law but increased its scope: Their “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring” enabled forced sterilisations. By 1945, around 400,000 people had been sterilised in hospitals – mainly those who were classified “socially conspicuous”.

Sterilisations were decided before so-called “Hereditary Health Courts”. Eugen Fischer and Otmar von Verschuer were enlisted as medical assessors. A separate office at the Institute was reserved for the paperwork.

The Institute also facilitated the sterilisation of several hundred African- and Asian-German teenagers. Because this was not officially legislated in the Nazi law, it was kept secret.

The sterilisation law drafted in the Weimar Republic was intended to allow voluntary sterilisations without doctors having to fear punishment. The Nazi law went further still, allowing sterilisations against the will of the persons affected. A list of indications determined those who should not have children. The list was largely based on the criteria put forth by Hermann Muckermann, a scientist at the Institute.

Agnes W.

Agnes W. (1894–unknown) grew up in Berlin, first in foster care and later with her mother who worked as a seamstress. Agnes worked nights helping her mother. By fourth grade, Agnes had to leave school because she could not keep up with her lessons. From that point on, she worked in factories. She married at the age of 22, but her husband died only two years later. Agnes W. had three children; a fourth child died shortly after birth. She married again in 1934.

In 1935, the district doctor applied for Agnes W. to be sterilised. He diagnosed her with “congenital imbecility”. As a result, the Berlin Hereditary Health Court ordered her sterilisation. Agnes W. appealed twice. The Higher Hereditary Health Court dismissed these appeals. The rejection was signed by the Director of the Institute, Eugen Fischer, a medical assessor for the court. In November 1936, a district doctor carried out the forced sterilisation of the 42-year-old. We have no photograph of Agnes W.

Agnes W.’s objection to the decision of her sterilisation, 1935

Federal Archives, Berlin

Agnes W. defended herself against the diagnosis of “congenital imbecility”: “If that were the case, I would probably have been deprived of the right to raise my children years ago … For two boys and without any help raising them I have managed to go through life … as an honest, hard-working person who has never had a criminal record”.

Racist Forced Sterilisations

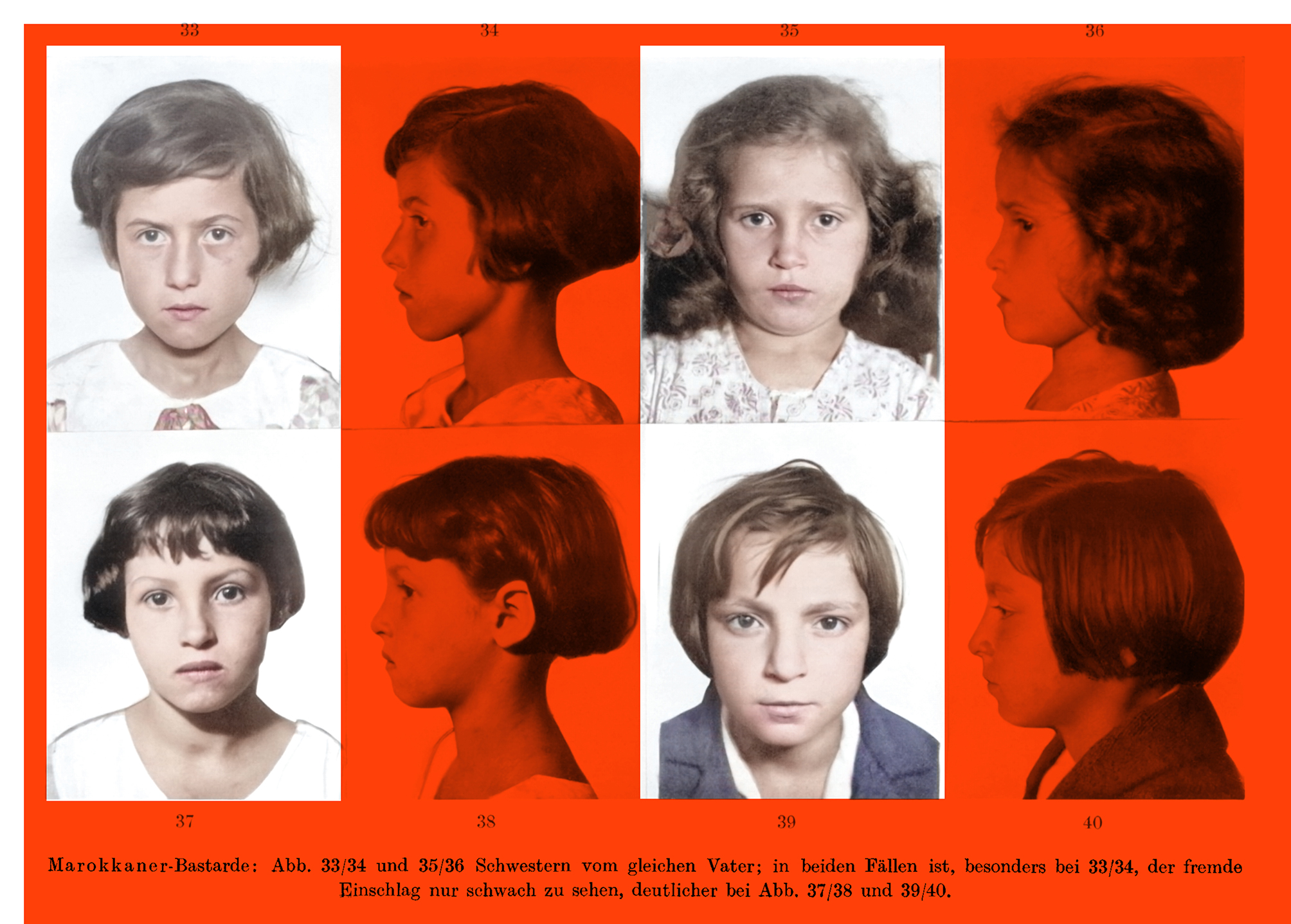

These anthropological photographs show the sisters Erna (top left) and Hildegard (top right), as well as Irmgard (bottom left) and Susanne (bottom right). In July 1933, they and 35 other children were measured and photographed by Wolfgang Abel, a member of the Institute, on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior. These children all had German mothers and fathers of African or Asian descent. Their fathers belonged to French or U.S. troops stationed along the Rhine after the First World War. Abel classified the children as “weak in mental and physical health”. In 1937, his “examinations” were used as justification for sterilising at least 400 children in a secret operation. Records attest that Erna, Hildegard, and Susanne were forcibly sterilised. It is highly probable that Irmgard suffered the same fate.

From: Wolfgang Abel, “On European-Moroccan and European-Annamite Race Mixing”, 1937

Berlin State Library

Excerpt from the rejection of Erna K.’s application for compensation, 1955

Hessian State Archives, Wiesbaden

Erna K. (1922–unknown) is one of the children photographed by Abel. Later in life, she applied for compensation for her forced sterilisation. In 1955, the Compensation Authority in Wiesbaden informed Erna K. that her application had been rejected. They claimed it could not be proven that she had been “sterilised solely because of her race”. Erna K. had waited almost six years for this reply.

1. In Germany, victims of the 1937 sterilisation campaign were confronted with compensation authorities that knew nothing of the secret scheme. Moreover, people of African and Asian descent were not at all recognised as victims of Nazi persecution. The authorities denied that they had been sterilised for racist reasons.

2. Erna K. would also not have received compensation if she had been sterilised according to the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseased Offspring”: for decades in the Federal Republic, the law was not recognised as an injustice. It was not until 1980 that those affected could receive one-off compensation payments. And only in 1998 were the court orders for sterilisations officially repealed. In the GDR, victims of sterilisation were not officially recognised as victims of the Nazi regime.

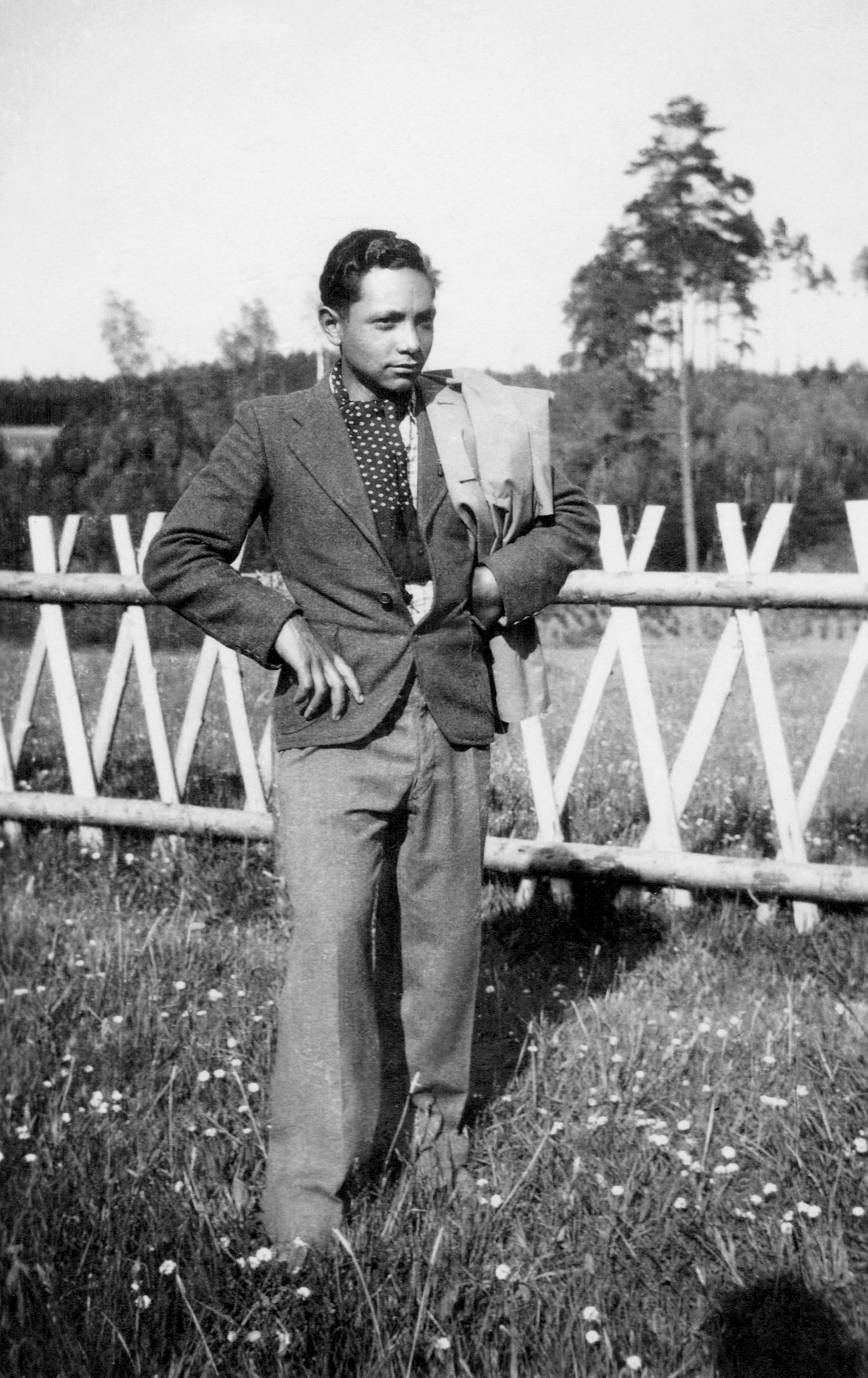

Josef Kaiser

Josef Kaiser was born in Speyer in September 1921 to Maria Kaiser, an unmarried 18-year-old German. His father was René José de Capelas, a Malagasy officer in the French army. Josef, his mother, and his younger sister Susanne lived in Speyer, together with his grandparents. As a child, Josef worked at the circus. He finished school in 1935. He was denied vocational training under the Nuremberg Laws.

In 1937, Maria Kaiser – under pressure from the Health Department – agreed to the sterilisation of her children. Susanne was sterilised in June 1937. Josef fled several times. He was finally seized by the Gestapo and sterilised the same day at the municipal hospital in Ludwigshafen.

In 1943, Josef Kaiser was forced to work in the Nazi construction group “Organisation Todt” and later he was taken prisoner by the British. In 1945, he married Herta Grimm. To this day, Herta is campaigning for recognition of the injustice suffered by her husband. Josef Kaiser died in 1991.

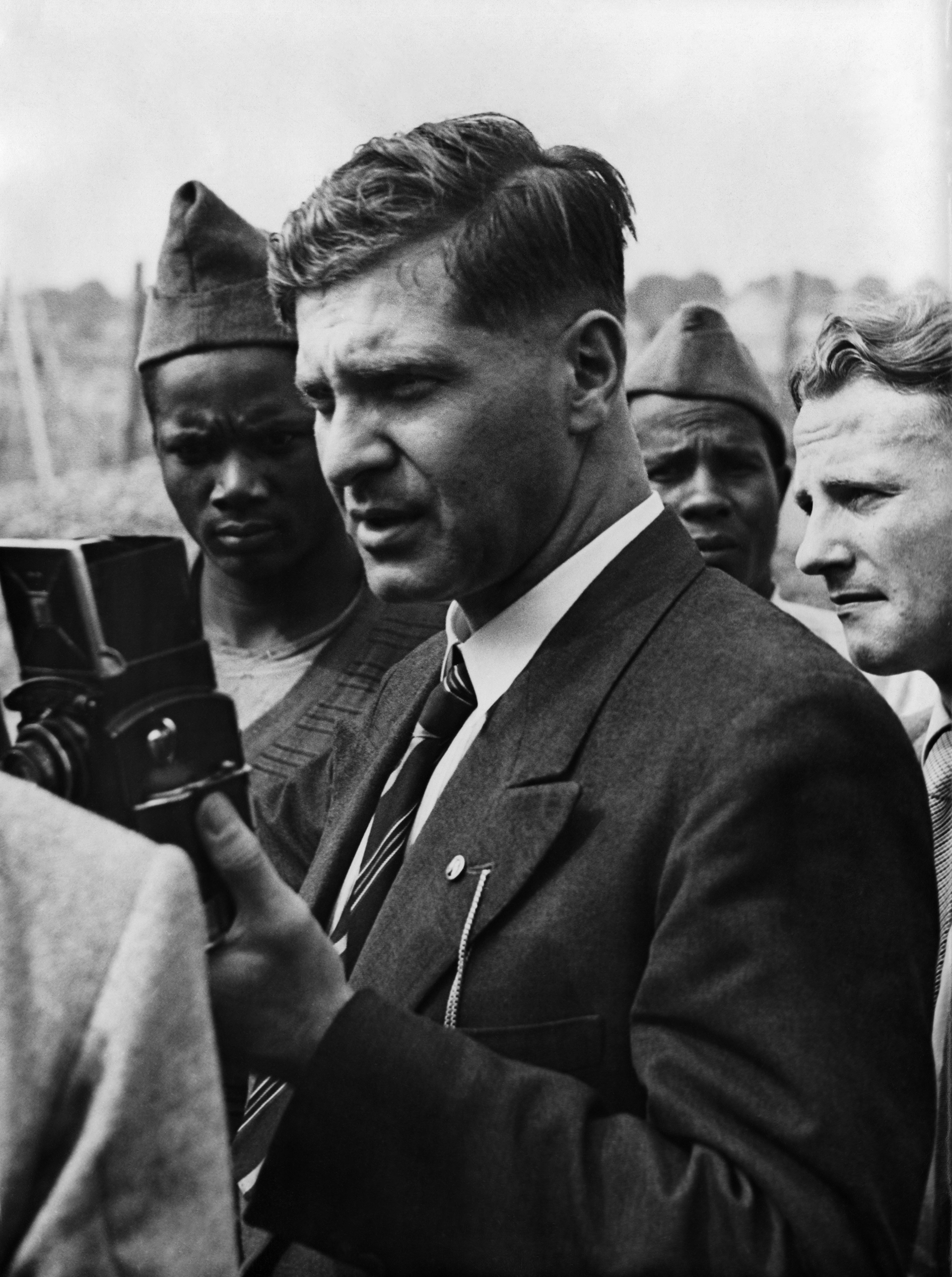

Josef Kaiser, c. 1939

Private Archive of Herta Kaiser/Michael Lauter

Notification from the Speyer Health Department on the whereabouts of Josef Kaiser, 1937

State Archive Speyer

The authorities made great efforts to track down the African-German and Asian-German children who had been identified for sterilisation. Josef Kaiser fled but he was eventually arrested during a visit home.

Luzie und Cäcilie Borinski

Luzie and Cäcilie Borinski were born in Koblenz in 1920 and 1922. They grew up with six other siblings and their mother Margareta. The sisters did not know their father Prodencio Dole Mendiola. He came from the Philippines and served with the US troops stationed in Koblenz after the First World War. Luzie and Cäcilie’s siblings did not have the same father.

As children of Asian descent, Luzie and Cäcilie were forcibly sterilised in 1937. Luzie wanted to marry her partner Heinrich Bell. However, the Nazi authorities repeatedly denied her the required “certificate of suitability for marriage” (Ehetauglichkeitszeugnis). It was not until shortly after the Second World War that Luzie and Cäcilie married their respective partners. The sisters remained terrified of doctors for the rest of their lives.

Luzie and Cäcilie were important caregivers for their nieces and nephews. Luzie took care of her younger brother’s first child as her own son, and later took in his son as well. Cäcilie died in 1993, Luzie in 2002.

The sisters (from left) Cäcilie, Elfriede, and Luzie Borinski, 1955

Private Archive of Gisela Johannsen

Minutes from the meeting deciding on the sterilisation of Cäcilie Borinski, 1937

Federal Archives, Berlin

In May 1936, a commission in Koblenz decided that Cäcilie Borinski should be sterilised. The decision was taken in her absence. Cäcilie’s mother had agreed, very likely under duress. Herbert Göllner, an employee of the Reich Health Office who had completed his doctorate under Institute director Fischer, was a member of the commission. Cäcilie was sterilised in June 1937 at the University Women’s Hospital in Bonn. (416)

Was it all over after World War II?

Video commentary by

Tahir Della, Initiative of Black People in Germany

Margret Hamm, Association of Victims of National Socialist “Euthanasia” and Forced Sterilization

3:28 min.

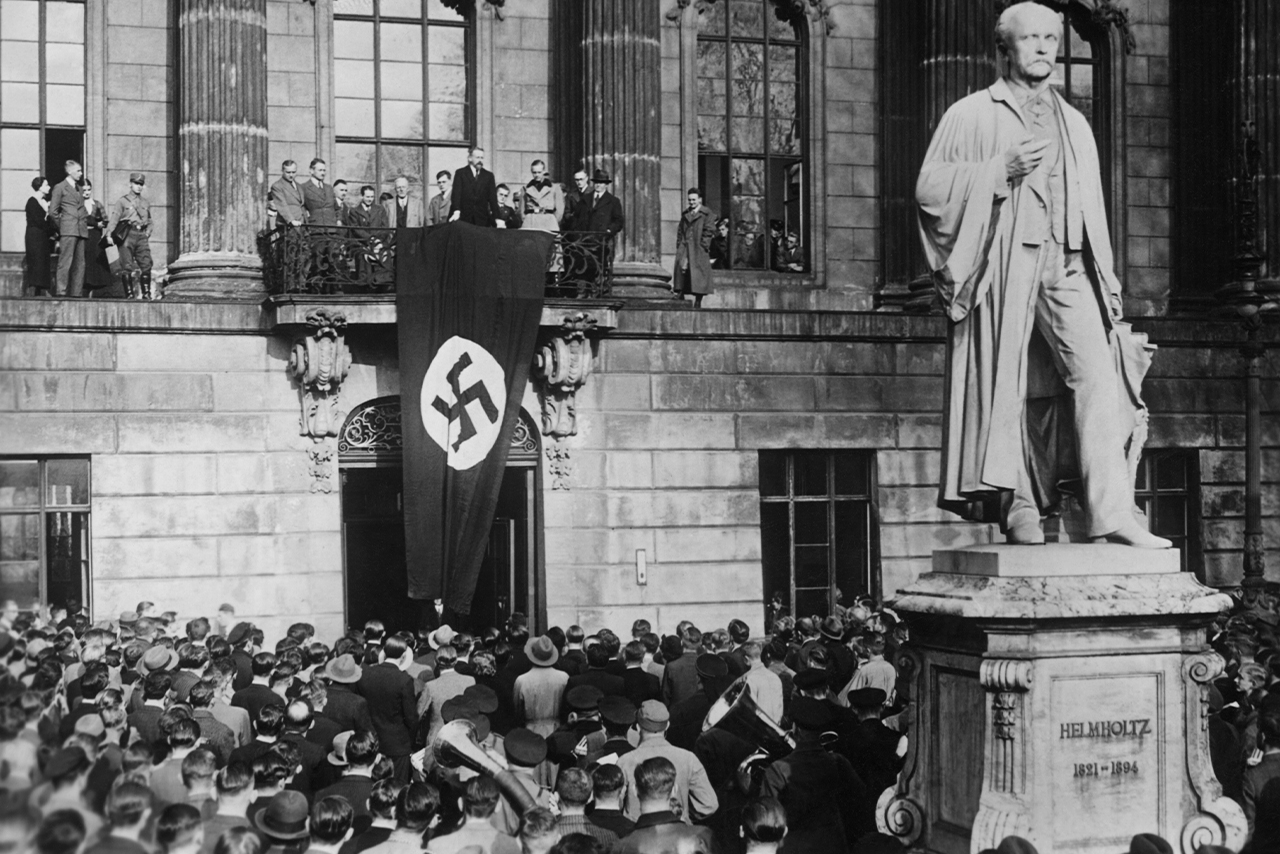

Wolfgang Abel

The physician Wolfgang Abel (1905–1997) worked at the Institute from 1931, after receiving his doctorate. From 1940, he headed the Department of Racial Studies. In 1943, he also became professor for racial biology at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin (today’s Humboldt Universität). Among other things, Abel researched the heredity of human skull shape and facial features, and he searched for markers of what anthropologists constructed as different “races”. Abel’s study of African-German and Asian-German children in 1933 led to their forced sterilisation.

Abel was a member of the Nazi Party and the SS. Already as a student, he had taken part in anti-Semitic attacks in Vienna. After 1945, Abel worked as an artist in Austria, where he died in 1997.

Scientists continued to research African-German children after 1945. Walter Kirchner claimed that their “intellectual capacity” would remain low, in the doctoral thesis he submitted to the Freie Universität Berlin in 1952. His doctoral advisor and supervisor was the former Institute member Hermann Muckermann, who headed a succeeding institute at Ihnestraße 24 from 1948.