SCIENCE

FOR

THE STATE

“Science and politics are always engaged in a dynamic relationship with one another: politics relies on science to underpin certain policies. And science can benefit from political interests. This dynamic also influences research content and practice.”

Sheila Weiss, historian

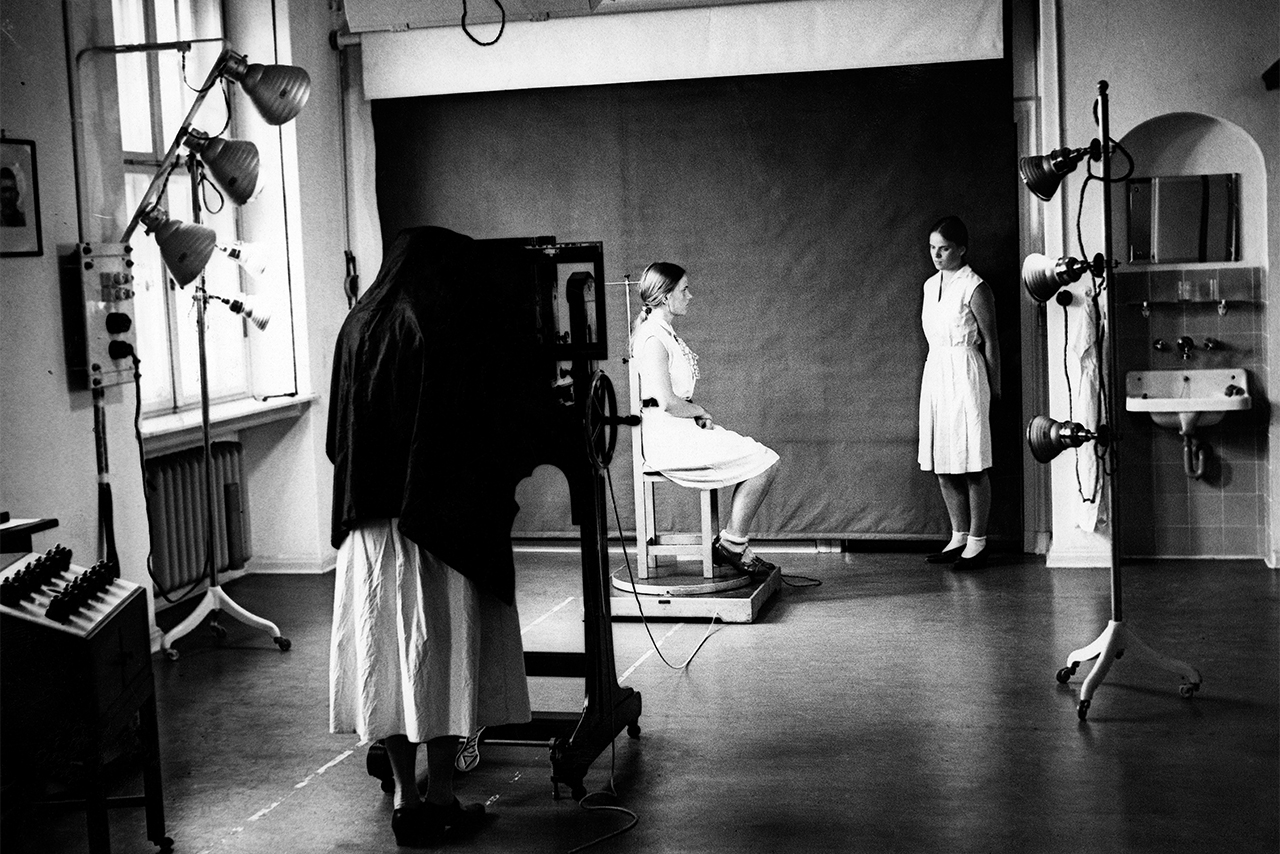

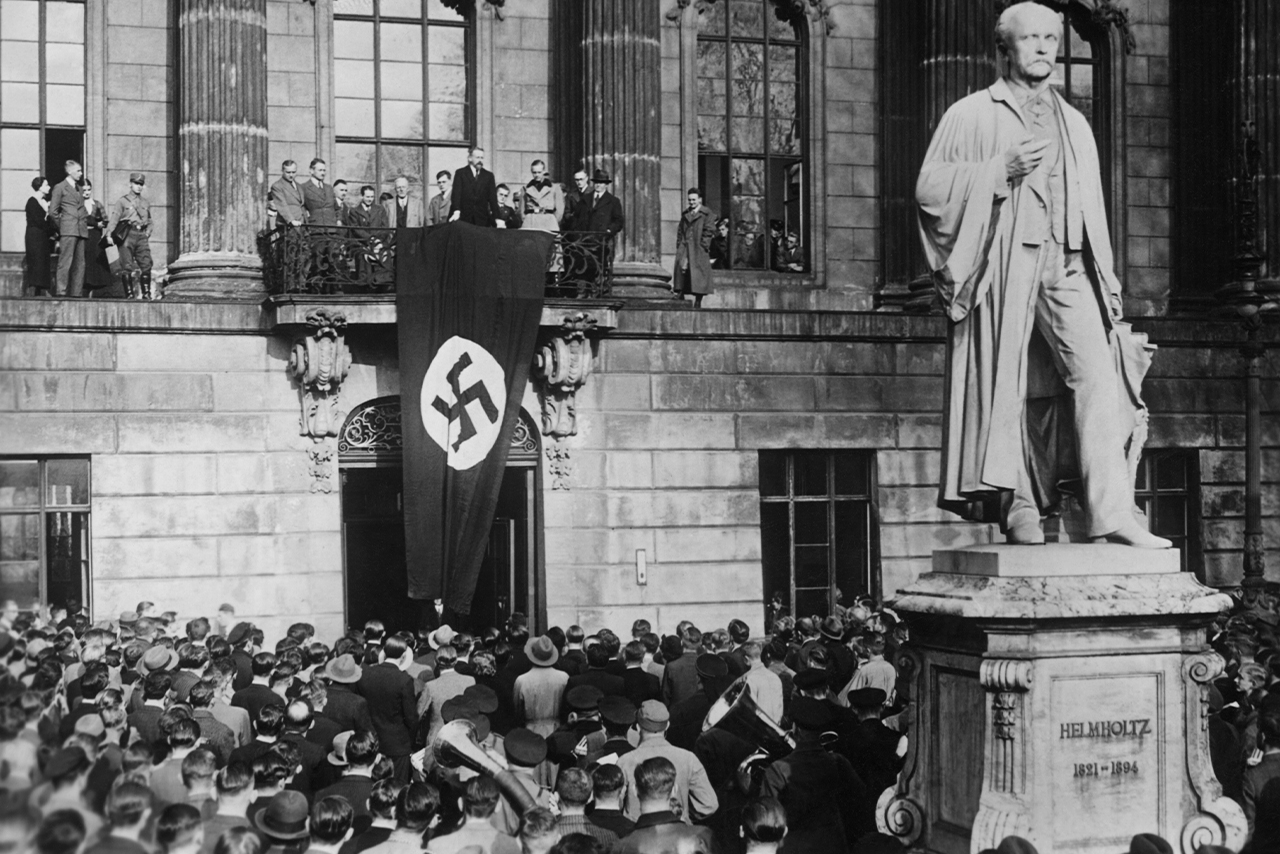

Today, there still is a lecture hall on the ground floor of Ihnestraße 22. It was there that members of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics held training courses for doctors and government officials on the principles of heredity. The idea behind this was that eugenic policies could only be developed and implemented through a proper understanding of heredity. Eugenics declared certain parts of the population desirable and others undesirable based on their genes.

These training courses provide evidence that research and politics were closely linked at the Institute. The government encouraged scientific research as a solid foundation for its population policy measures. In turn, the Institute profited directly from the state’s interest through financial support.

In March 1933, 60 government officials from various ministries came together for a week of training in “hereditary theory and eugenics”. Such courses had already been offered during the Weimar Republic and continued under National Socialism.

1

Hermann Muckermann regarded the declin ing birth rates in Germany as a danger. Based on demography as a statistical “population science”, he argued that families classified as “healthy” and “high-performing” should have more children. To do this, they needed financial support.

2

Otmar von Verschuer portrayed research on blood types as an innovative approach in the field of heredity studies. With this approach, he believed he could differentiate identical from non- identical twins. Additionaly, Verschuer sought to establish an alleged “racial affiliation” of individuals based on their blood.

3

Muckermann sought to prevent individuals deemed disabled or “mentally ill” from having children. He therefore advocated for their “institutionalisation”, which meant their placement in asylums. However, due to the high costs involved, he saw an alternative: the sterilisation of these individuals.

4

Throughout his research, Institute Director Eugen Fischer focused on exam ining the physical advantages and disadvantages that he believed were due to what he called “racial crossings”. He also cautioned that such “racial crossings” could jeopardise the supremacy of White people.