HEREDITY

RESEARCH

―

POPULATION

CONTROL

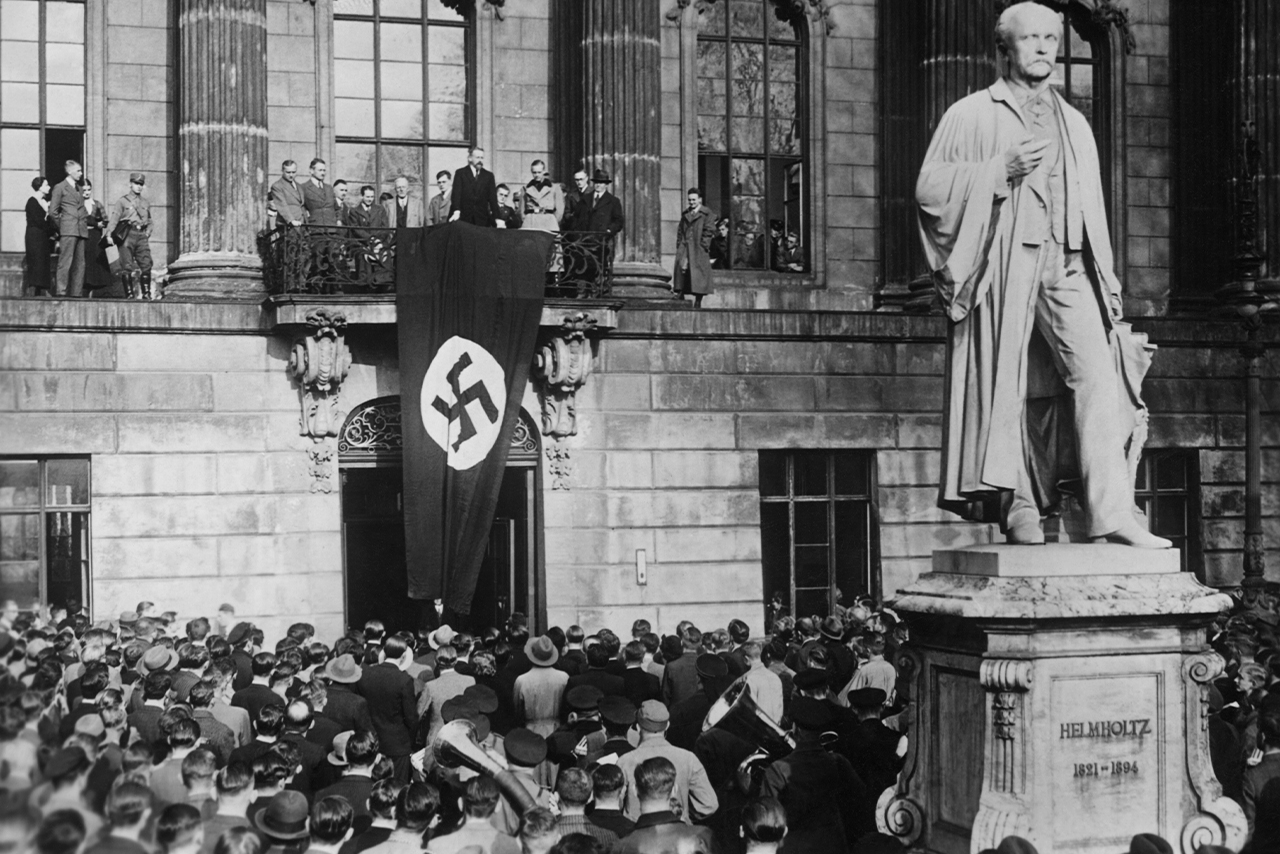

How does heredity work in humans? What role do genes play, and how important are environmental factors on human development? These were the central research questions at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics. The Institute began its work in 1927, as part of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (now the Max Planck Society). Initially, the Institute was comprised of the three separate departments from which its name derived: “Anthropology”, “Human Heredity”, and “Eugenics”.

The concept of eugenics had broad support in the Weimar Republic, among social democrats and right-wing nationalists alike. Proponents of eugenics believed that people with a diagnosed hereditary illness or disability should not have children, and that eugenic politics could serve as a means for the state to reduce the cost of social welfare and healthcare. From its inception, the Institute aligned itself with such policies and used them for its benefit. During the National Socialist period, Institute personnel were involved in the process of “selecting” and exterminating human beings.

“Anthropology”

Anthropology (Ancient Greek “ánthrōpos” – human, “logía” – study) is the study of human origins and human development. By measuring body parts, anthropologists constructed the concept of different human “races”. Eugen Fischer, Head of the Anthropology Department, however, believed that what he deemed “mere skull measuring” was insufficient. His own work combined such practices with genetic research, a method he called “Anthropo-Biology”. Fischer’s work nevertheless persisted in classifying humans into unequal races.

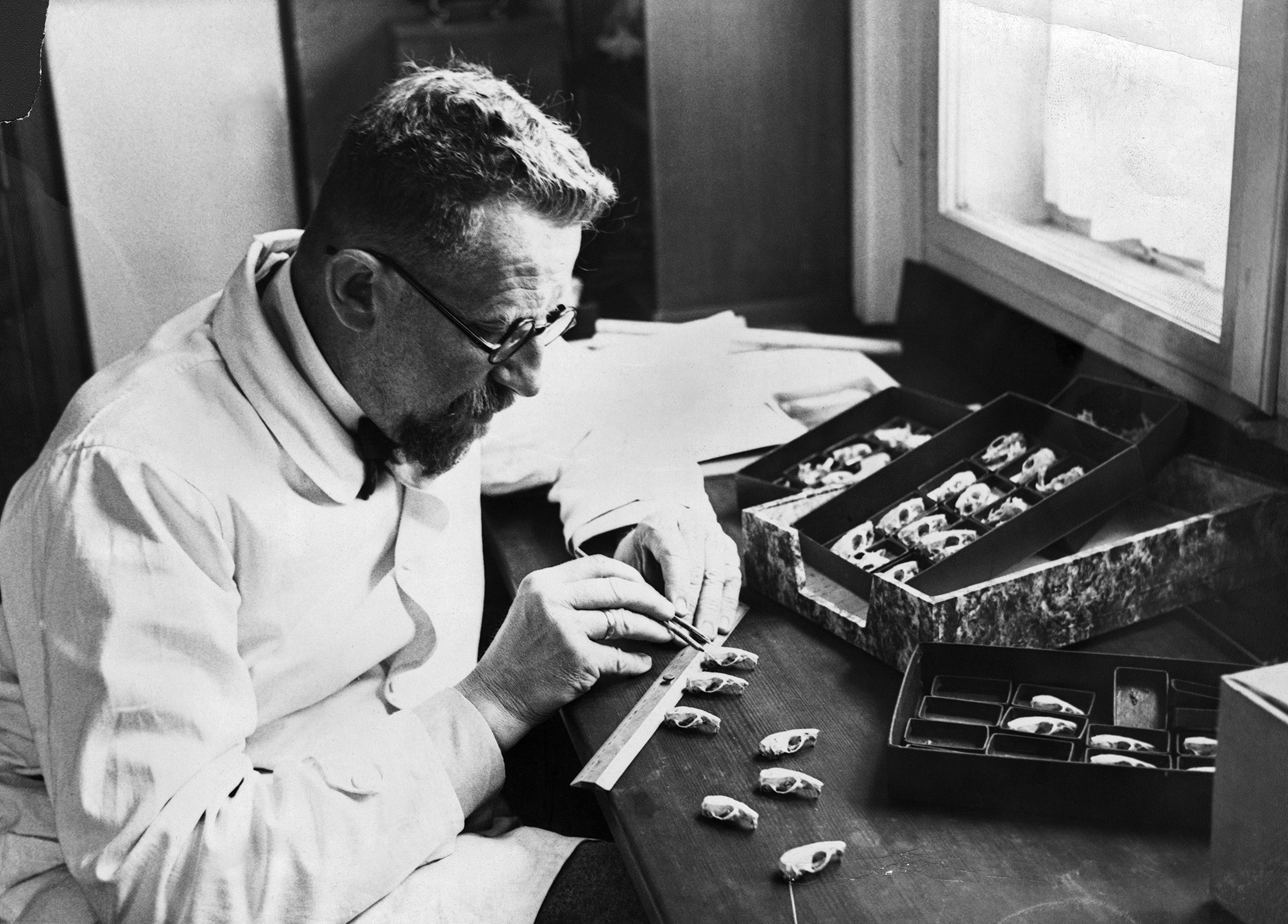

With this illustration of “long” and “round skulls”, Eugen Fischer intended to support his theory of supposed “hereditary racial differences”. At the same time, he took into account recent research indicating that environmental factors such as nutrition also influenced the shape of the skull.

The photo depicts Eugen Fischer at his desk measuring rat skulls. In the early 1930s, based on these animal experiments, Fischer concluded that a vitamin-rich diet produces longer skulls.

“Human heredity”

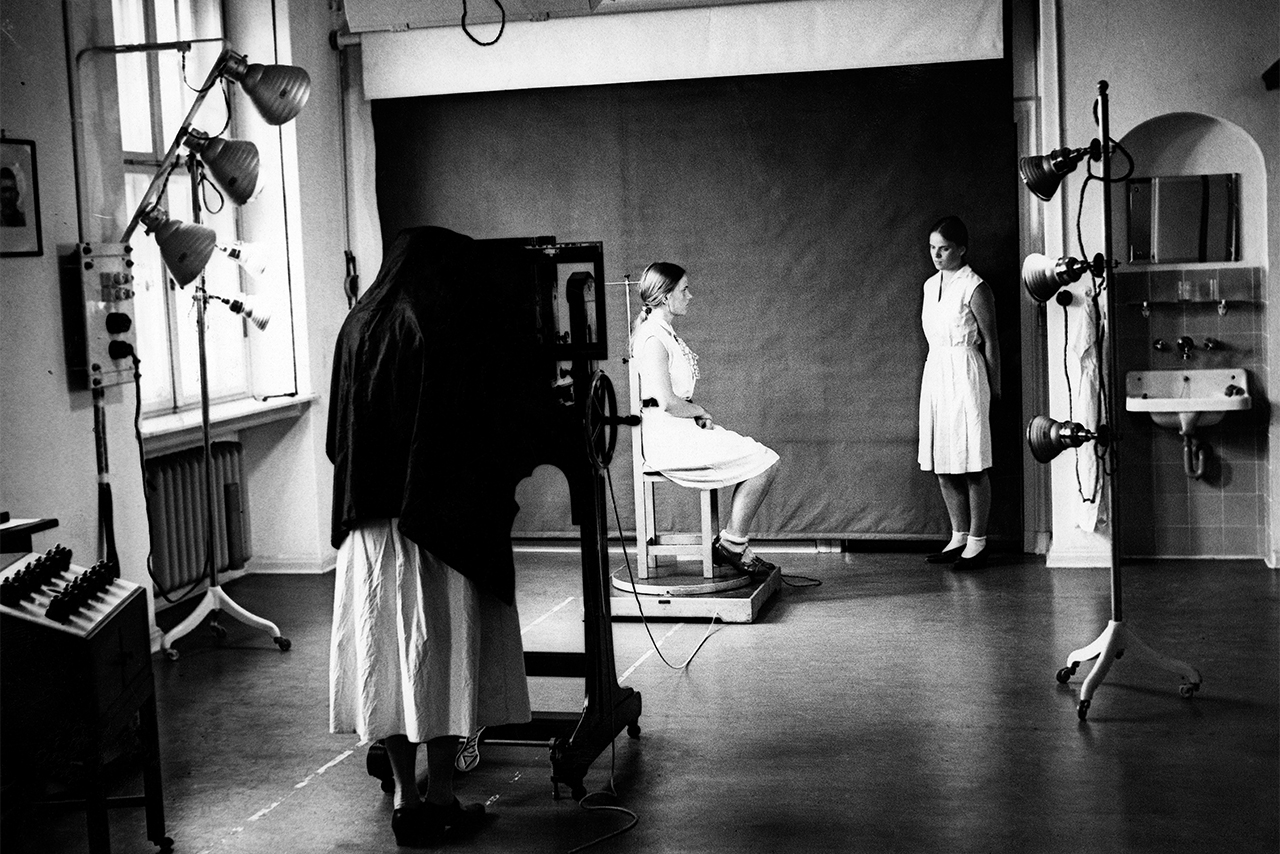

Under Otmar von Verschuer, the Department of Human Heredity applied state-of-the-art methods to conduct foundational research in human genetics. They intended to decipher hereditary mechanisms operating inside the body by means of external observation. Until the mid-1930s, their focus was on the comparative studies of twins.

This photograph documenting an examination of twins was taken in 1928, shortly after the Institute opened. Otmar von Verschuer compares the eyes of the two children using an “eye colour chart guide”. The “twin method” was considered a breakthrough in heredity research at the time. The children’s names are unknown.

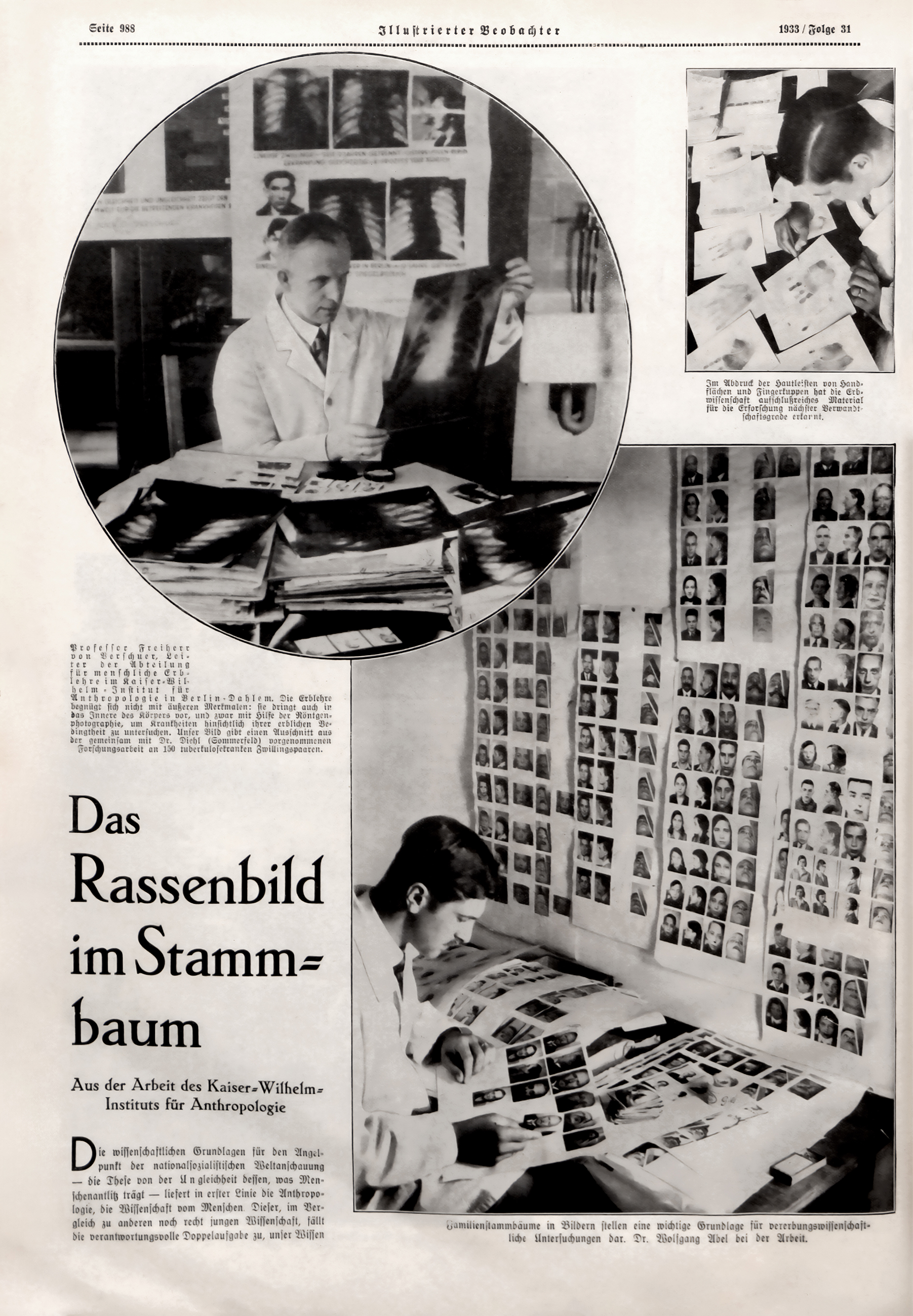

“Research on human heredity […] reaches into even the innermost part of the body”, states the text from 1933. Under Nazi rule, “hereditary theory” presented itself as an innovative science that could serve a policy of “selection”. The collage of images shows scientists analysing X-rays, handprints, and photographs. Some of the people examined were stigmatized as “hereditarily ill” or “inferior”.

“Eugenics”

Eugenics (Ancient Greek “eũ” – good, “génos” – birth) is the alleged science of “good breeding”. The Department of Eugenics at the Institute conducted very little research of its own. However, Hermann Muckermann, the Department Head, was active in promoting the eugenic principle: People he classified as “healthy” and “productive” and therefore deemed to be of “good hereditary disposition” should have more children. People he stigmatised as “hereditarily ill” on the other hand, should be sterilised.

In 1930, Muckermann used this diagram to illustrate what he saw as a worrying trend: professors had fewer children than the average “rural population”. The eugenicist saw university teachers as an intellectual elite with valuable hereditary dispositions who did not reproduce sufficiently.

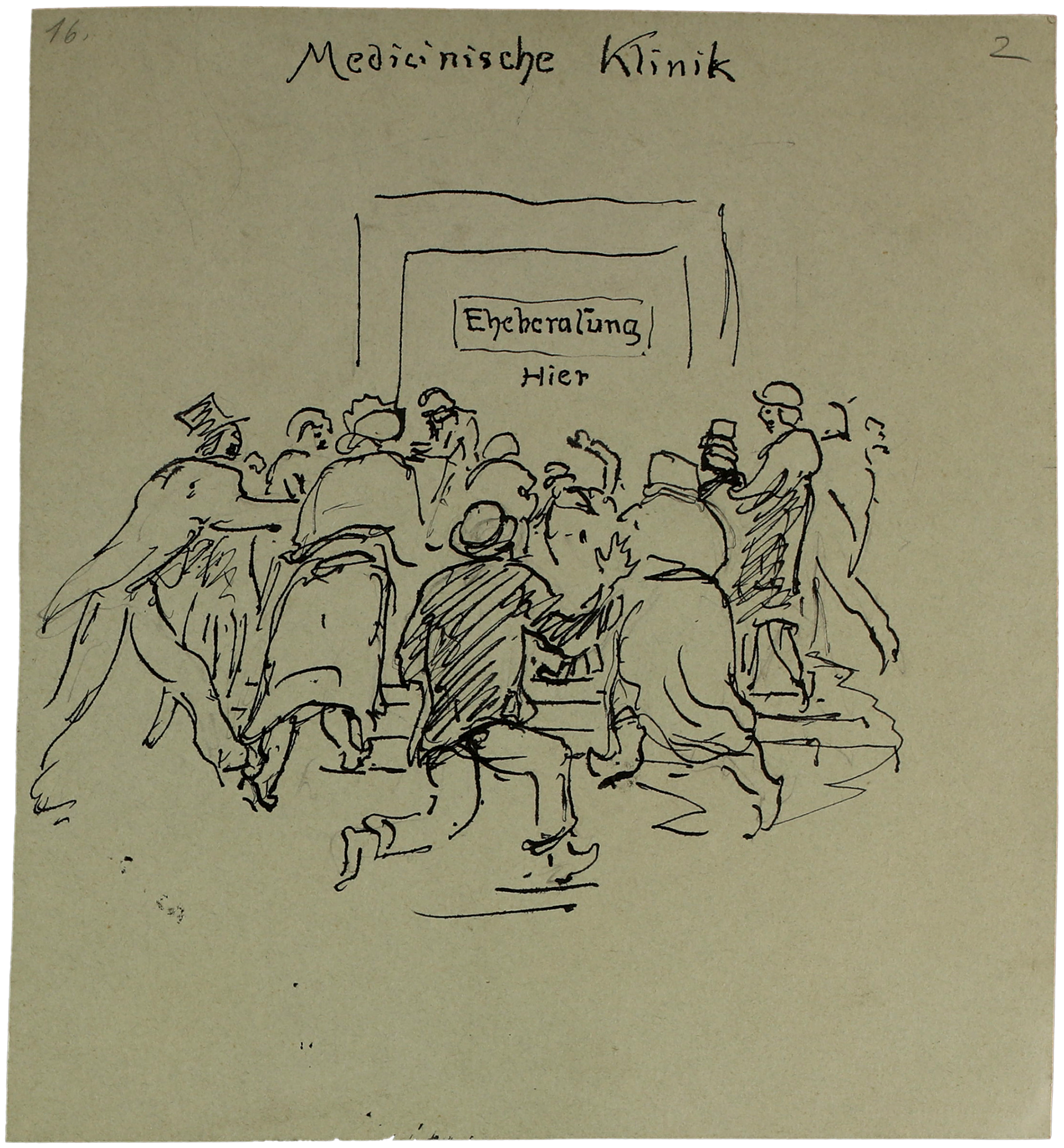

A crowd in front of the “Marriage Counselling Centre”: Otmar von Verschuer received this cartoon for Christmas in 1934 from the staff of the Polyclinic for Hereditary and Racial Hygiene in Charlottenburg, which he headed. There, couples suspected of having “hereditary diseases” were advised against marriage.

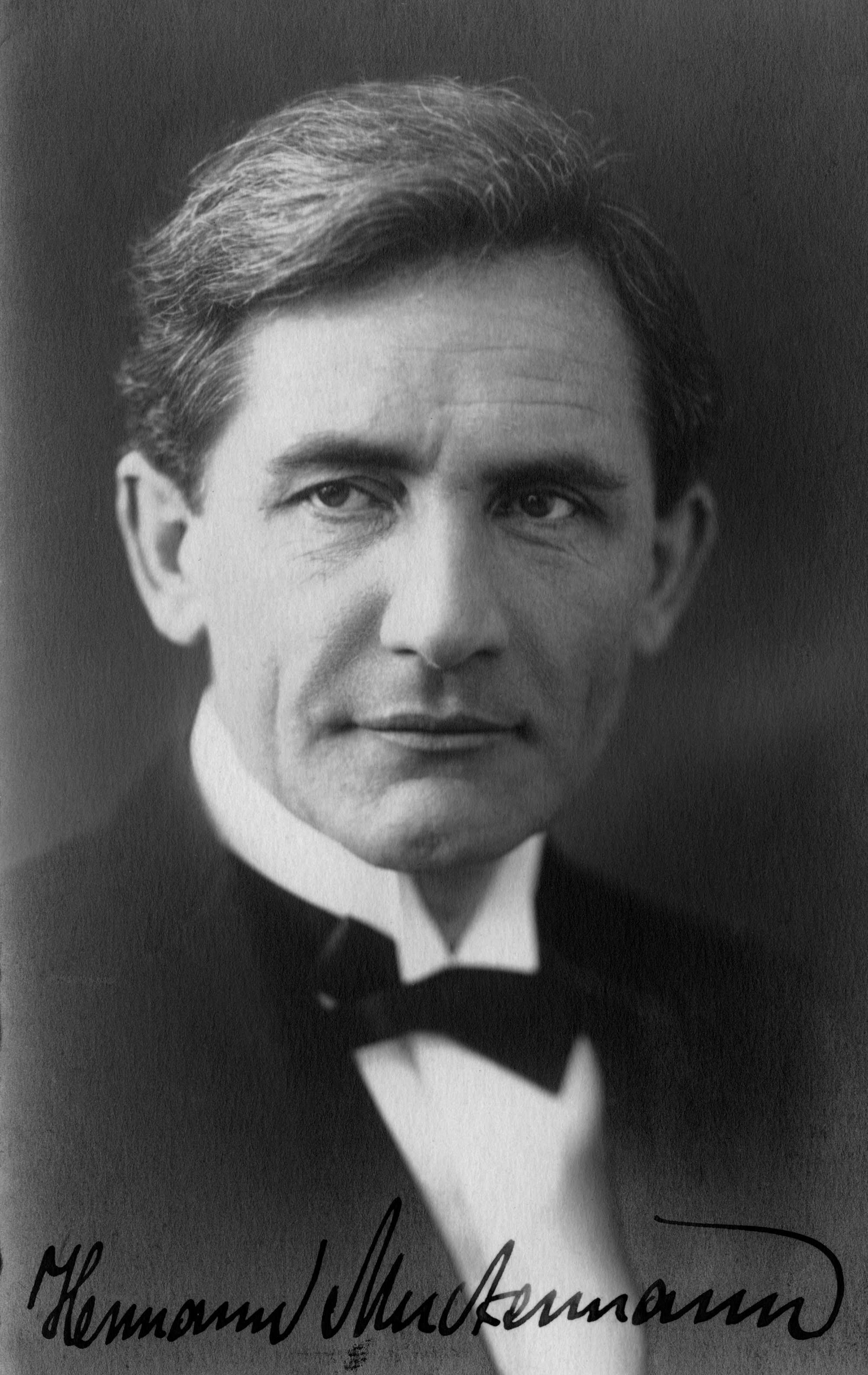

Hermann Muckermann

Biologist and Catholic priest Hermann Muckermann (1877–1962) was an early advocate for eugenics, and a popular travelling lecturer and author. In 1927, Muckermann became Head of the Department of Eugenics. However, by 1933, Muckermann was forced to leave the Institute: Due to his catholicism, he was deemed politically unreliable by the Nazis.

After the Second World War, Muckermann ran the small Institute for Applied Anthropology. Based at the former Director’s Villa at Ihnestraße 24, it operated until 1961 and was long financed by the Max Planck Society. Muckermann, a professor at Technische Universität Berlin who also taught at Freie Universität, continued to promote the idea that people with alleged “hereditary illnesses” should voluntarily refrain from having children.

Demonstration with the slogan “Inclusion Not Selection”, 2019

Matthias Heinzmann

In 2019, activists held a demonstration for “Inclusion Not Selection”. They opposed the funding of prenatal blood tests by health insurance companies. Associations of disabled people warn that these types of tests will lead to fewer children being born with a trisomy, in favour of aborting pregnancies whenever a disability is diagnosed. Those who consciously decide to have a disabled child would increasingly have to justify themselves. Could it be that “voluntary eugenics” has prevailed?

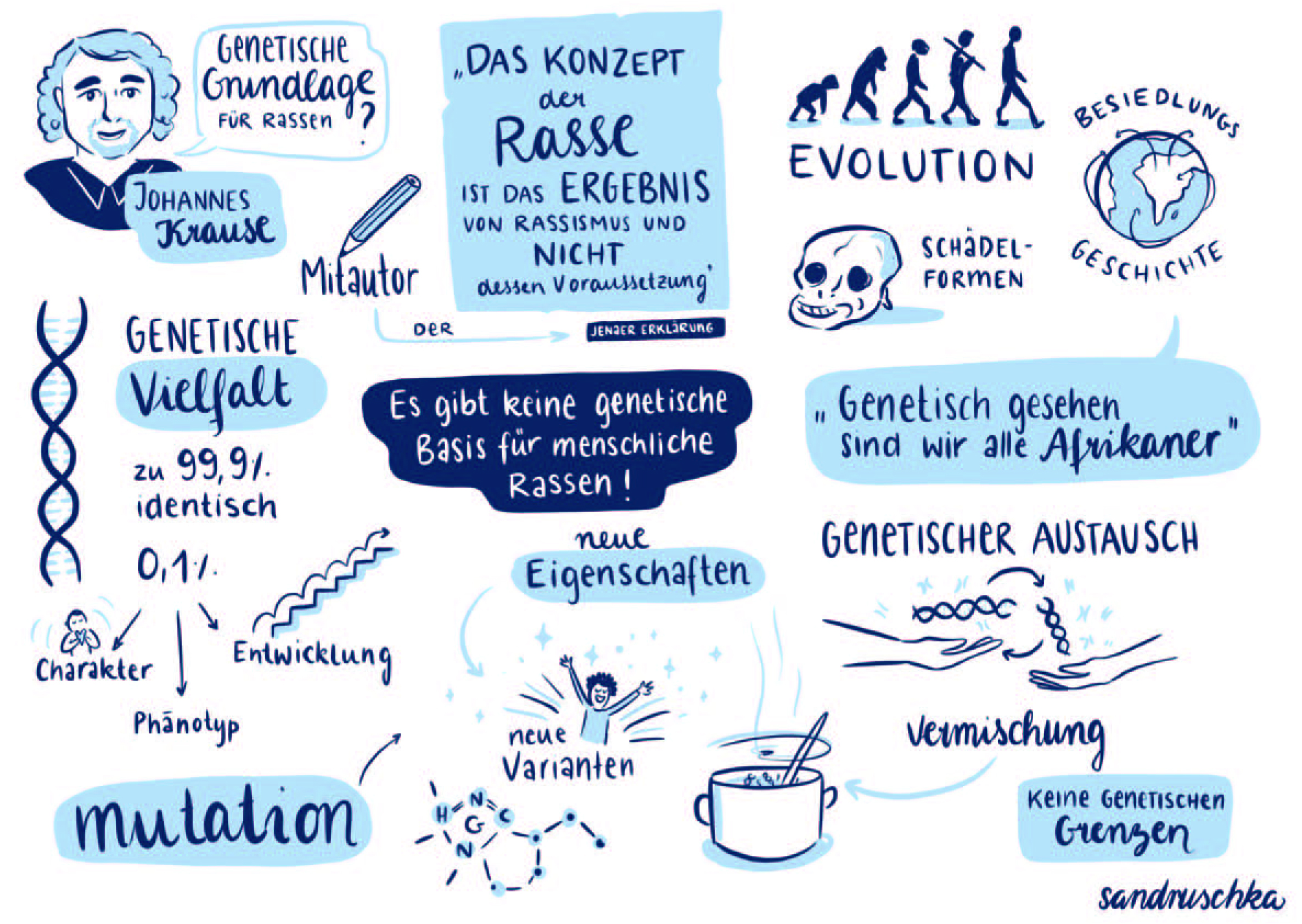

Graphic for a lecture on the “Jenaer Erklärung” (Jena Declaration), 2021

sandruschka/Salea Rackwitz, CC BY-ND 4.0

In a lecture, Johannes Krause used this illustration to explain his criticism of the idea of “race”. In 2019, the geneticist had published the “Jenaer Erklärung” together with other scientists. They criticised the concept of “race” as being dangerous and entirely redundant. Whichever genetic differences may be used to justify “race” are arbitrary, they said. “Race” is a “construct purely of the human mind”.

It was the personality and research profile of its directors that determined the agenda of each Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Therefore, in addition to generous facilities at the Institute, the director was also given a prestigious villa with a garden, where he received guests from both the world of science and politics. The first to live in the villa was Founding Director Eugen Fischer with his family, followed by his successor Otmar von Verschuer in 1942. Today, the building is home to offices of the university.