SCIENCE

AND

MASS MURDER

“Science per se knows nothing of ethical boundaries. The boundaries have to be negotiated by society.”

Hans-Walter Schmuhl, historian

Nazi extermination policies provided scientists at the Institute with new research opportunities, which they enthusiastically accepted. Scientists saw forced labour and extermination camps as ideal research grounds. Free from ethical and legal limitations, they could collect data, conduct human experiments, and obtain body parts of those murdered.

The Institute maintained particularly close ties to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Doctor Josef Mengele, who practised there, had received his doctorate from Otmar von Verschuer, the last director of the Institute. From 1943 on, Institute staff had Mengele send them blood samples from prisoners, and preserved body parts of those murdered at the camp.

The Mechau Family

The family of Otto Mechau (1881–1943) and Auguste Mechau (1891–1943) lived in Hamburg until 1939, and then in Oldenburg. Sinti increasingly faced persecution under National Socialism. In 1938, Otto Mechau was imprisoned intermittently in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. After a “detainment decree” was issued in October 1939, Roma and Sinti were no longer allowed to leave their place of residence.

On 8 March 1943, police officers surrounded the family’s home. At least five adults and nine children were transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. According to the research programme of Karin Magnussen, a scientist at the Institute, doctors there performed experiments on members of the Mechau family.

All members of the family who were deported to Auschwitz were murdered. Only two of Otto and Auguste Mechau’s sons survived the National Socialist genocide of the Roma and Sinti.

Family photo of the Mechau family, 1930

Private Archive of Hugo Mechau/Günter Heuzeroth Collection

The family photo from 1930 shows Otto Mechau in the centre, with his wife Auguste (Rahli) Adele Mechau, née Bamberger (1891–1943) seated to the left. Hugo Mechau (1909–1989, second from right) was able to save these and other photographs. He survived the National Socialist regime.

Auguste Laubinger with her children Fridolin and Lydia, before 1943

Private Archive of Hugo Mechau/Günter Heuzeroth Collection

In this photo, you can see Auguste (Wella) Laubinger (1911–unknown) – a daughter of Auguste and Otto Mechau – with her children Fridolin (1941–1943) and Lydia (1935–1944). It must have been taken shortly before their deportation to Auschwitz. Auguste Laubinger, like her daughter Lydia, was a victim of Magnussen’s research. All three were murdered in Auschwitz.

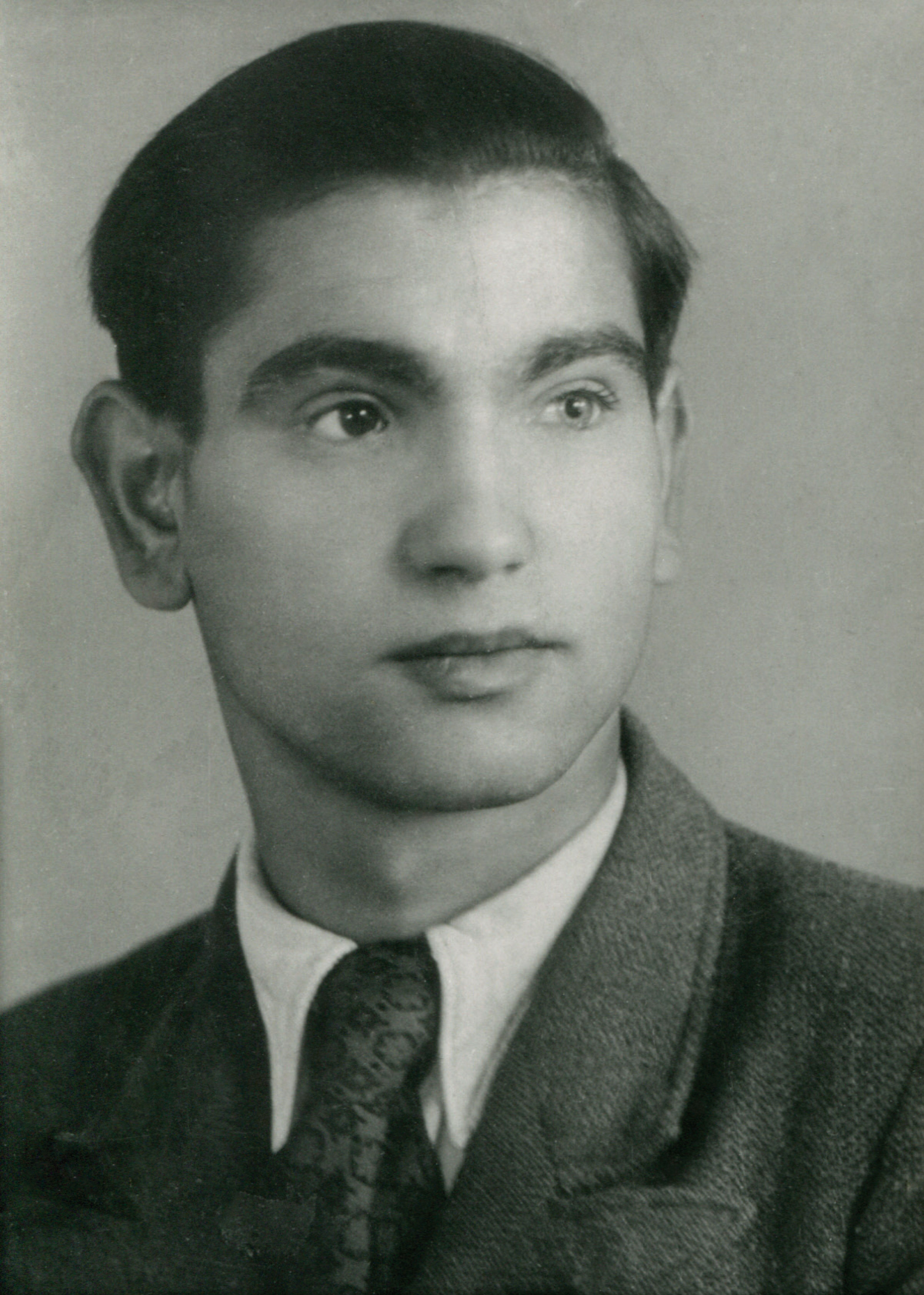

Balduin Mechau, date unknown

Private Archive of Hugo Mechau/Günter Heuzeroth Collection

Auguste and Otto Mechau’s son Balduin Mechau (1925–1944) was also a victim of medical experiments. The record of Balduin Mechau’s death in Auschwitz-Birkenau is dated 28 February 1944. Magnussen’s documents suggest that she obtained specimens of his different coloured eyes.

Karin Magnussen

Biologist Dr. Karin Magnussen (1908–1997) had already joined the Nazi Party in 1931 and remained a racist and anti-Semite all her life. In 1936, she published the training book “Tools for Racial and Population Policy”.

She received a fellowship at the Institute in 1941. In 1943, she was promoted to Assistant. Her research focused on heterochromia – differently coloured eyes. At first, she experimented on rabbits. Between 1943–1944 she capitalised on her connections to Auschwitz: Josef Mengele sent heterochromic eyes from members of the Mechau family to Magnussen at the Institute as specimens.

During the process of denazification, she was classified as a “Mitläufer” (follower) in 1949. Magnussen did not continue her scientific career, but instead worked as a biology teacher in Bremen.

In 1943, Karin Magnussen published on “The Determination of the Colour and Pigment Distribution of the Human Iris”. Her research focus was heterochromia – different coloured eyes. At first, she experimented on rabbits. In 1943 and 1944, she made use of her connections to Auschwitz: Josef Mengele sent specimens of heterochromic eyes from members of the Mechau family to Magnussen at the Institute.

After Karin Magnussen’s death, several so-called “kinship charts of the M. family” were found in her files. This version, drawn by Magnussen, contains the names and birth years of members of the Mechau family. Over three generations, Magnussen systematically entered the eye colouring of the family members. In this way, she sought to trace the inheritance of different coloured eyes.

As a result of the experiments in Auschwitz, Karin Magnussen wrote an essay on heterochromia in 1944, which has not survived. Around 1980, she wrote a new text in which she intentionally omitted the experiments on the members of the Mechau family. She gave the text to the Max Planck Society. She wanted the text to be “left to the next generation of scientists”.

1

2

Magnussen claims that her human experiments were intended to heal people. In fact, she accepted the murder of people and conducted research on their physical remains.

3

4

5

How did discrimination against Sinti and Roma continue after the Second World War?

Video commentary by

Anja Reuss, Historian and former Political Advisor at the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma

3:43 min.