RESEARCH

ON ANIMALS

―

RESEARCH

ON HUMANS

The small building behind the Institute building was employed by the Institute to house laboratory animals; scientists used rats, rabbits, dogs, and chickens for breeding experiments. In 1936, another stable block was built which no longer exists today.

Researchers here were interested in human heredity, and animals served as stand-ins for human beings. Because animals had no legal rights, research on them had no limitations.

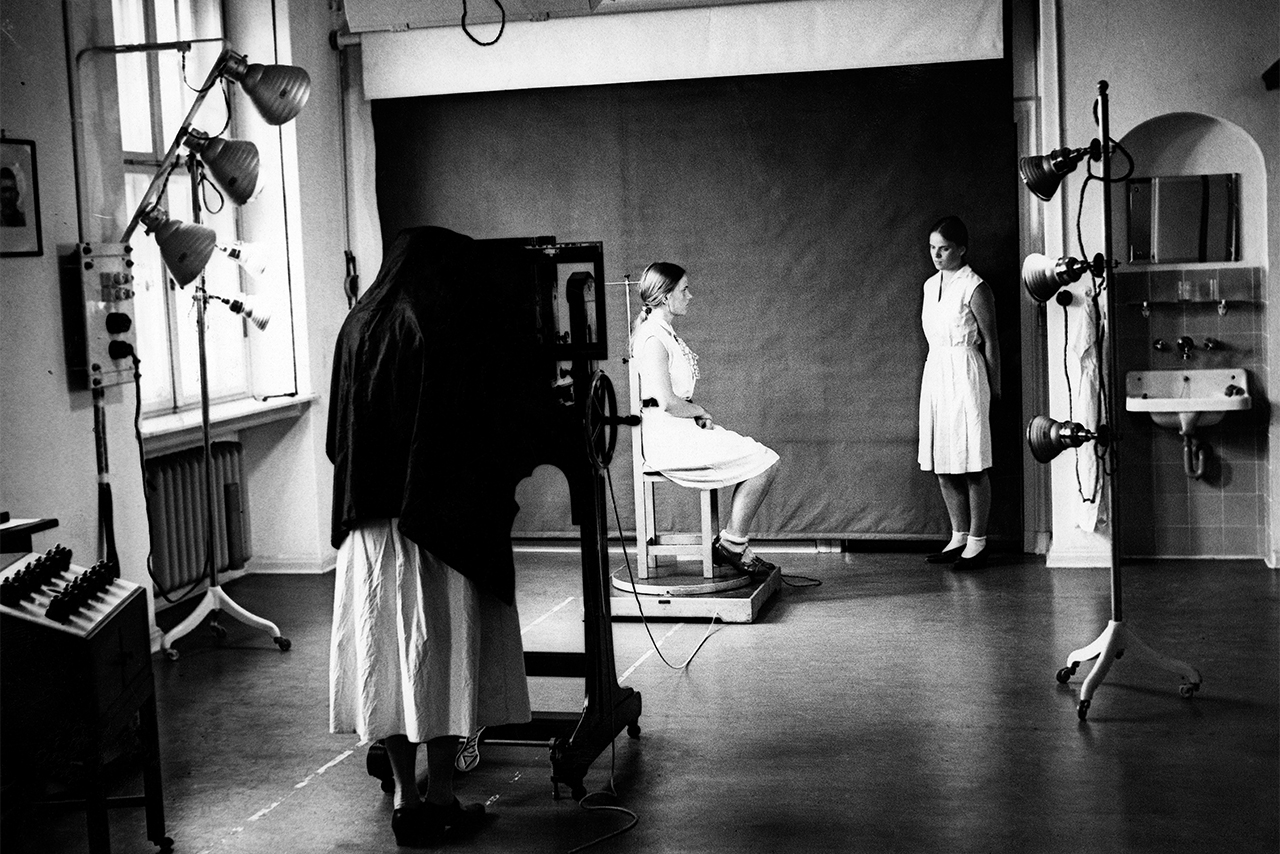

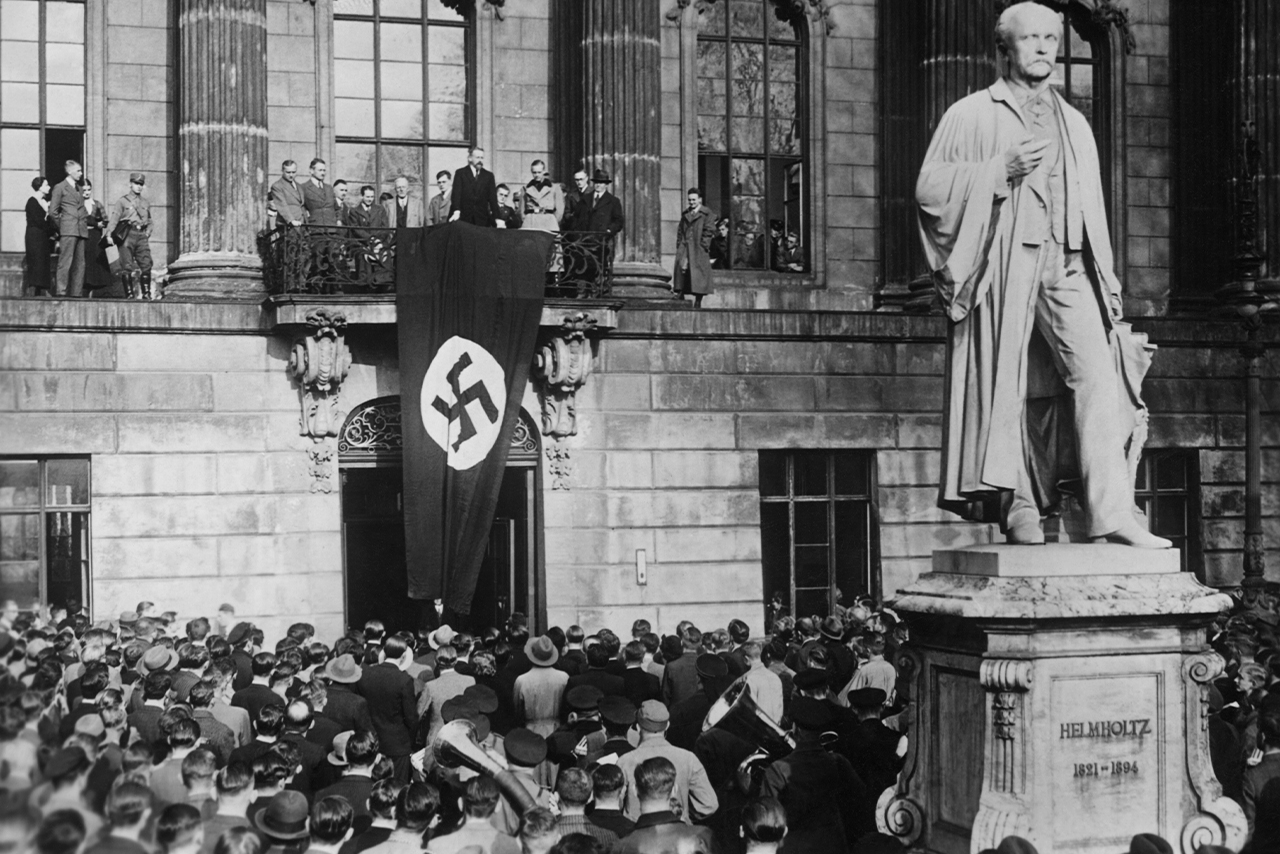

During the Weimar Republic, scientists conducting research on human subjects still needed to obtain their consent. Under National Socialism, researchers were given almost unlimited access to people in camps and sanatoriums. These people did not have the right to object.

Group photo in front of the stable for laboratory animals: In a seemingly rural idyll, Institute staff posed next to the freshly planted plum tree. From 1998 to 2017, the building was used as the student-run “Rotes Café” (Red Café).

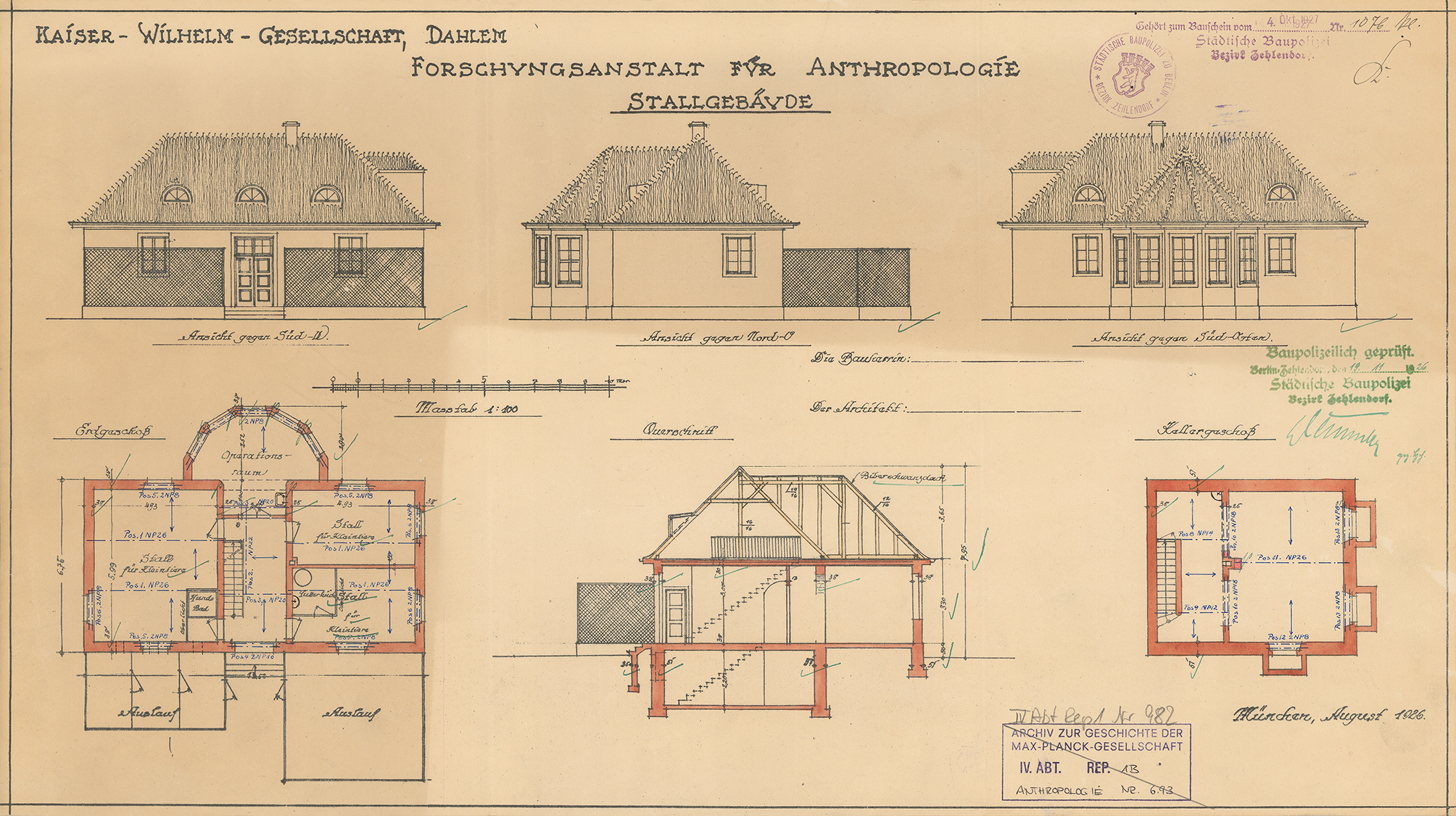

The building plan shows the structure of the small stable from 1927. There were three rooms for small animals such as rabbits and chickens as well as a dog bath and outdoor runs. The semicircular porch on the other side of the building served as an operating room. The limited dimensions of the stable show that there was no large-scale animal breeding in the early years of the Institute.

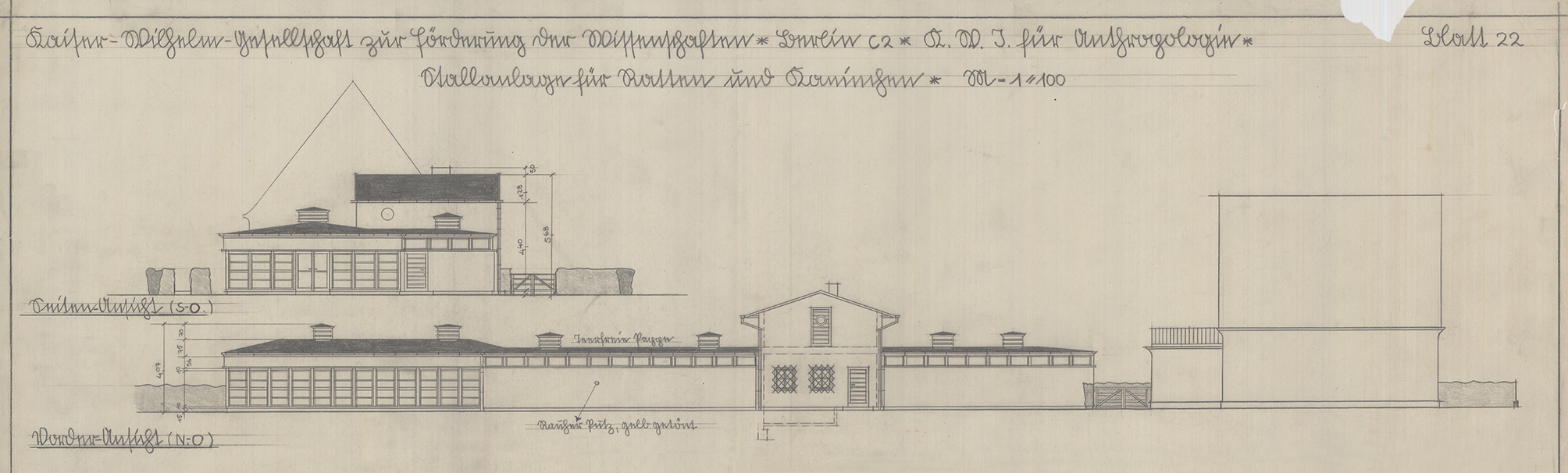

A large complex with stables was built directly next to the Institute grounds in 1935/36. The plan provided for a number of animal pens designed to house rats, rabbits and chickens. Directly in front of it – towards Ihnestraße – the Institute’s “Chauffeur’s House” was built. The buildings were later demolished and replaced by new ones.

Hans Nachtsheim

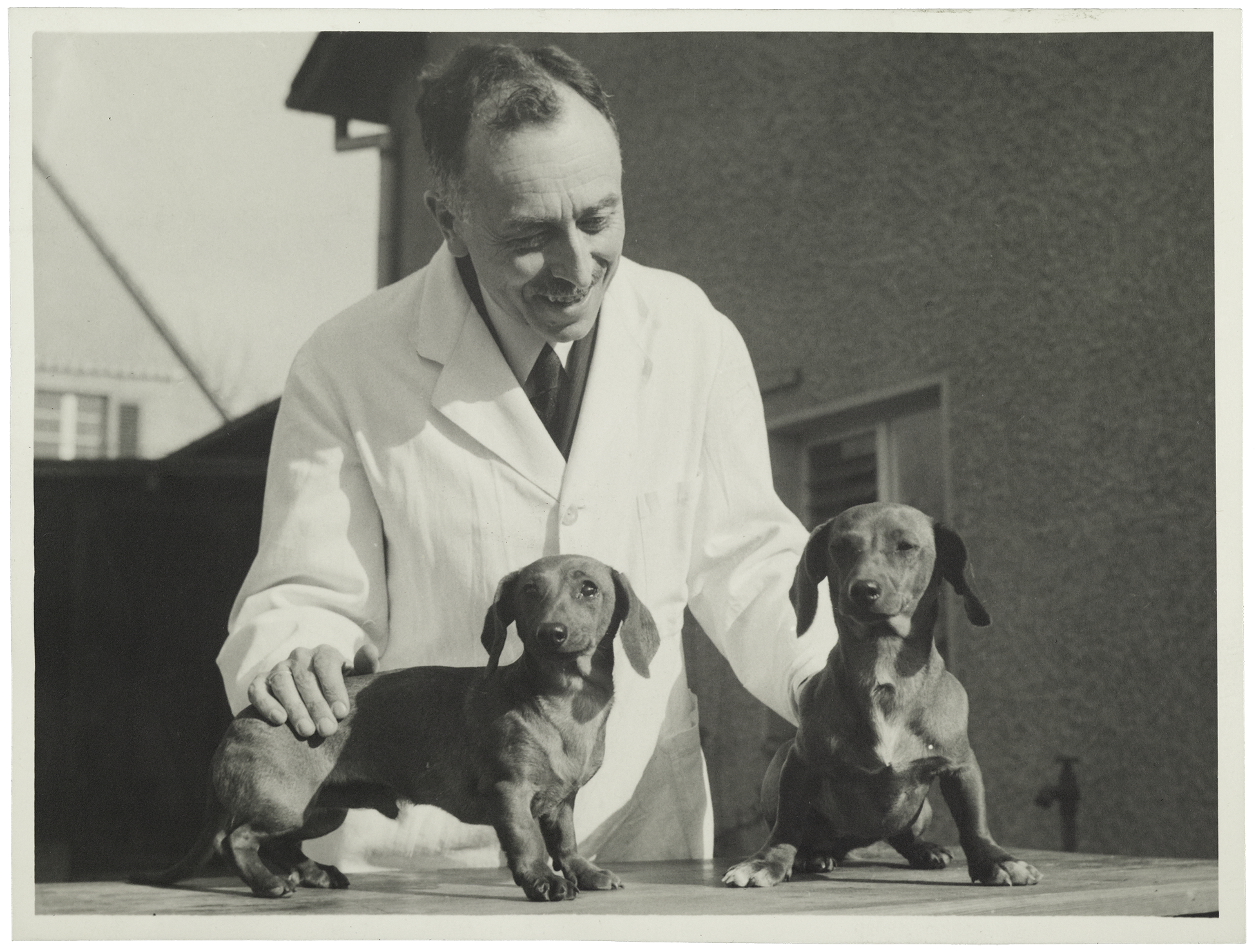

Zoologist and geneticist Hans Nachtsheim (1890–1979) took over the newly founded Department of Experimental Hereditary Pathology in 1941. Nachtsheim wanted to find out to what extent diseases could be traced back to heredity. His research included breeding “ill” and “healthy” rabbit populations. He also participated in experiments on humans.

After the end of the war, the U.S. authorities allowed him to continue working onsite, as he was deemed “politically uncompromised”. Nachtsheim used the remaining animals for research purposes and lived in the “Chauffeur’s House”. In 1949, he became a professor of biology at Freie Universität. There he established an institute for genetics, which he led until 1955. He was also appointed director of the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Genetics and Hereditary Pathology.

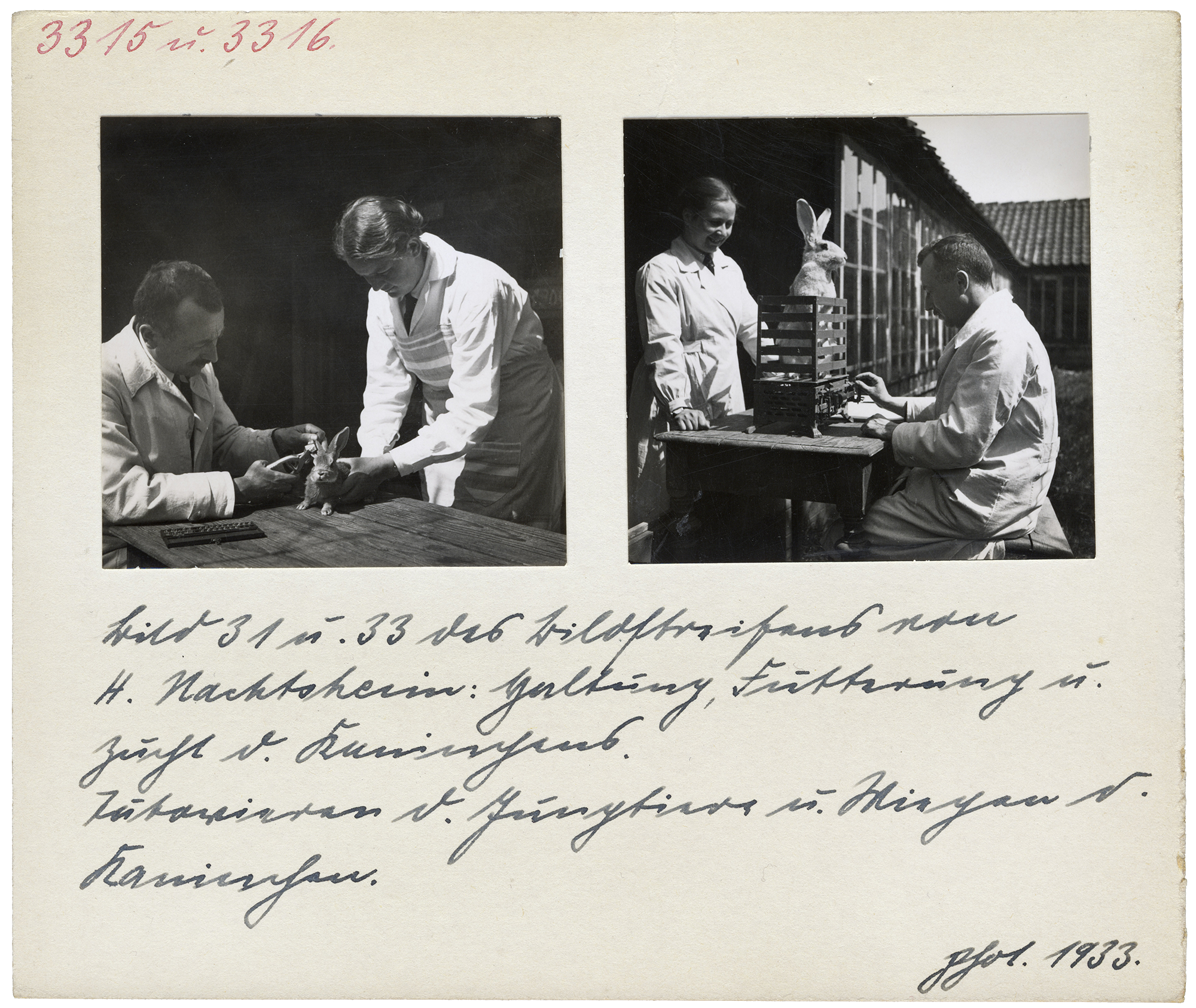

These pictures show Hans Nachtsheim before his days at Ihnestraße. Here, he is at the Berlin Institute for Hereditary Research in 1933, where he and an assistant tattoo and weigh a test rabbit. Among his experiments, Nachtsheim would later breed rabbits with a disease he called “hereditary epilepsy”. He would put the animals in decompression chambers which caused them to have seizures.

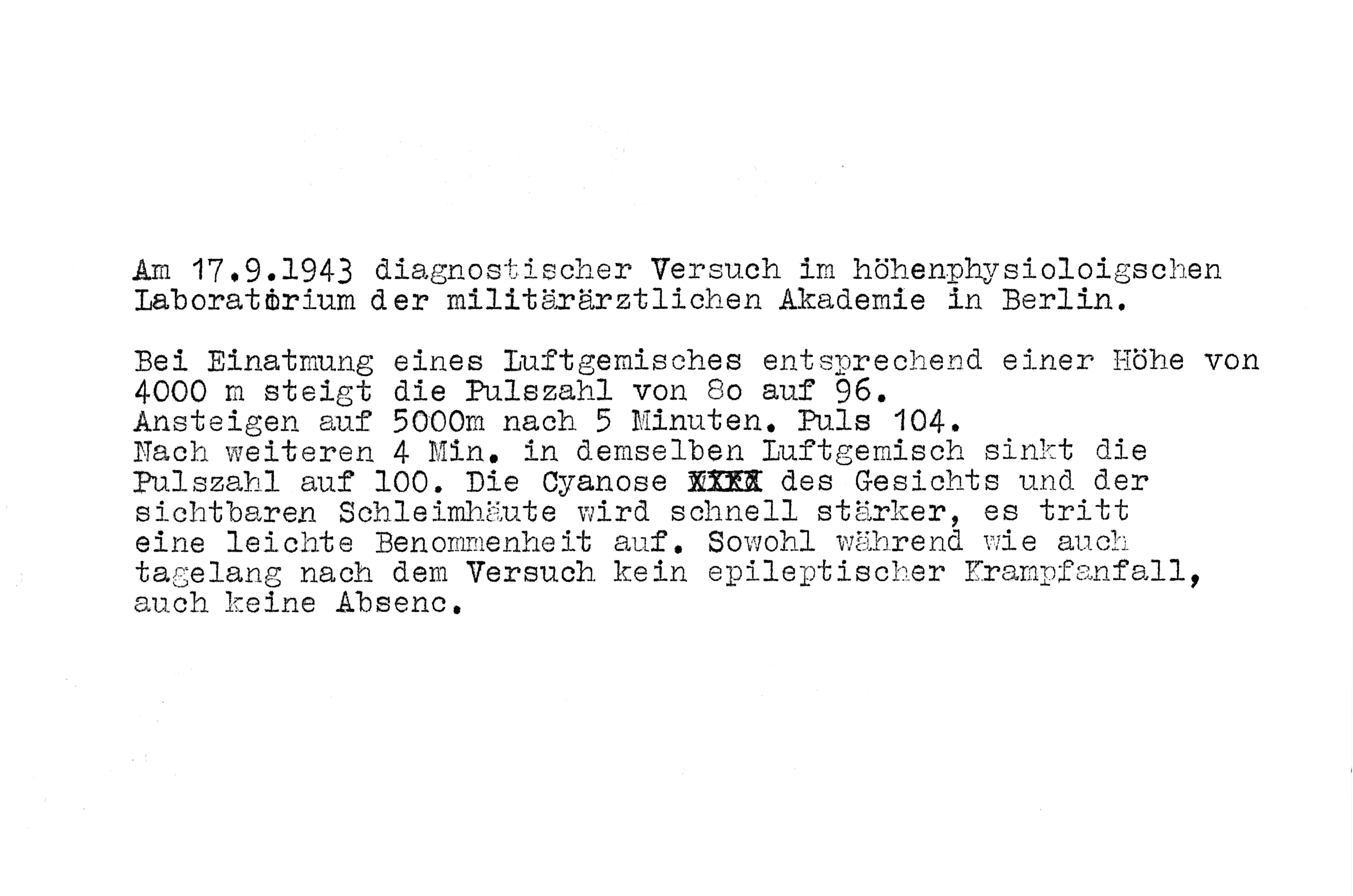

This report comes from the file of Hildegard K., an eleven-year-old girl who was admitted to the “sanatorium” Görden in 1941 with the diagnosis of “epilepsy”. In 1943, Nachtsheim put Hildegard inside a decompression chamber and reduced the oxygen supply, at great risk to her life. He wanted to test whether a lack of oxygen – as had previously been the case in experiments with rabbits – also triggered seizures in children.

The Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics at Ihnestraße 63–73 is the direct successor to Nachtsheim’s Department of Experimental Hereditary Pathology. In 1953, it became the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Genetics and Hereditary Pathology, headed by Nachtsheim. The Institute received its current name in 1964. Today, research on genome and genetic diseases is conducted here.